Northern High Plains cotton acres more than double in last 5 years

Experts expect growth to continue

Cotton acreage continues to boom in the High Plains north of Interstate 40, more than doubling in the past five years. And whether that is due to water savings or projections for improved profitability, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service specialists don’t foresee a slowdown in growth in the near future.

Since 2013, there has been a significant increase in cotton acreage in the Texas High Plains, said Jourdan Bell, Ph.D., AgriLife Extension agronomist, Amarillo.

Driving this acreage explosion is primarily the reduction in the saturated thickness of the Ogallala Aquifer in this region, which has resulted in declining irrigation well capacities, Bell said. As a result, producers are finding it harder to meet the full crop water demand of corn.

Because cotton is a drought-tolerant crop, it is an excellent companion crop for Texas High Plains irrigated acres, she said. Incorporating cotton into a corn rotation allows producers to concentrate irrigation on corn and maintain corn production goals while planting their remaining irrigated acreage to a drought-tolerant crop.

Of significance, new early and early mid-maturity cotton varieties are better adapted to this production region with improved yield potentials, Bell said.

Breaking down the numbers

“The most interesting commonality among the counties with the most growth is their location; four of the five are located north, or largely north, of the Interstate 40 corridor,” said Justin Benavidez, Ph.D., AgriLife Extension economist, Amarillo. “The growth in cotton acreage north of Amarillo is largely a result of agronomic factors and, one year of difficult planting aside, doesn’t seem to be slowing down.”

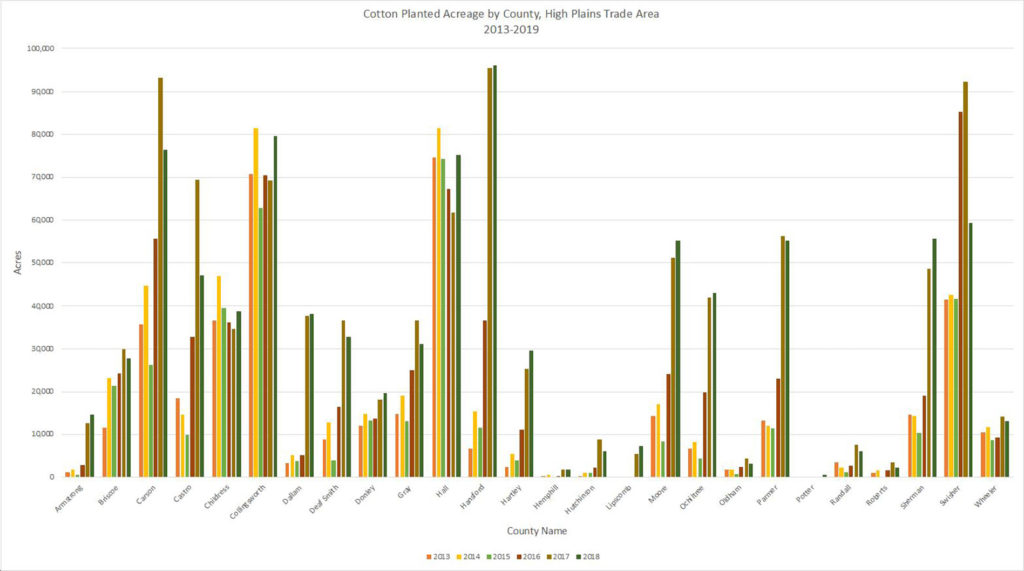

Between 2013-2019 total cotton acres in the northernmost 26 counties of Texas, referred to as the High Plains Trade Area, increased 126%, from about 404,000 acres to almost 915,000 acres.

This change in planted acres represents an average growth rate of 8.6% annually across the region. Excluding the challenges presented by prevented planting in 2019, the annual growth rate in cotton acreage from 2013-2018 was 18.1%, Benavidez said.

The change in acreage was not spread evenly across the region, he said. Five counties showed the most significant increase in cotton acres between 2013-2018. During this period, cotton production in Hansford, Parmer, Sherman, Moore and Carson counties grew 301%, to over 250,000 acres.

Even comparing the change from 2013-2019 and including the significant prevented-planting issues in 2019, acreage in the same five counties increased 128%, to over 100,000 acres, Benavidez said. The largest growth in cotton acres occurred primarily between 2016-2018. New cotton acres replaced corn and sorghum, both of which saw acreage declines in the region during that period but have since rebounded.

Cotton economics

Benavidez said the change in acreage between 2013-2018 resulted in an increase in cash receipts from cotton across the High Plains. In 2013, the region’s cotton cash receipts were $272 million. By 2018, that figure nearly doubled, growing to $519 million.

Final cash receipts figures for 2019 are not available yet, he said, but total cash receipts for corn and cotton combined increased from $886 million in 2013 to $997 million in 2018.

Hansford, Parmer, Sherman, Moore and Carson counties saw significant growth in their cash receipts from cotton, Benavidez said. Other northern Panhandle counties with significant growth in cotton cash receipts between 2013-2018 were Dallam and Ochiltree.

“There are also economic forces suggesting more cotton acres substituted for corn acres this year,” he said. “The ratio of December corn futures prices to December cotton prices is a commonly used early indicator of acres planted to cotton, and currently it indicates the projection for cotton profitability has improved relative to the projection of corn profitability.”

Benavidez explained on Sept. 3, the ratio indicated there would be between 9-11 million acres of cotton planted nationwide. On Feb. 10, that ratio had decreased, estimating between 11-13 million acres of cotton planted nationwide.

Cotton supplies and use

The World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates, WASDE, August projection was for a nationwide average cotton yield of 855 pounds per acre. By January, the nationwide yield was revised down to 817 pounds per acre, although projected yield went as low as 755 pounds per acre in December.

“WASDE also revised harvested acres down around 6%, from 12.64 million in August to 11.8 million in January,” Benavidez said. “Much of the yield and acreage revisions were due to production challenges in 2019 in the Texas High Plains.”

Another factor affecting cotton prices is a slight decline in use, however not as much as total production and ending stocks, he said. The decrease in supply with relatively stable demand led to an increase in price by as much as 11 cents per pound, indicating more producers may consider cotton when choosing between it and grains.

“With cotton becoming a more common choice in rotations on the High Plains and current commodity prices, it is likely there will be more acres planted to cotton this spring than last, even accounting for prevented and late planted acreage in 2019,” Benavidez said.

AgriLife Extension helps with High Plains cotton variety selection

Since 2014, AgriLife Extension has expanded its cotton programming efforts in the northern High Plains to meet producer needs, Bell said. Annually, Replicated Agronomic Cotton Evaluations, or RACE, trials are conducted across the state by regional agronomists in coordination with AgriLife Extension county agents and farm cooperators. The RACE trials provide producers an unbiased comparison of varieties being marketed in their respective regions.

“Variety selection is one of first decisions a producer makes each season,” she said. “So, timely variety trial data can assist with preplant variety selection.”

These large-plot replicated trials permit variety evaluation across multiple management and environmental conditions. This allows agronomists like Bell to assess variety stability.

“It is important that a variety is able to respond to favorable conditions as well as maintain production under tough conditions,” she said.

Since 2014, Bell and county agents across the northern High Plains have conducted 38 RACE trials to evaluate early and early medium maturity varieties. With the region considered a short‐season cotton production region, variety selection is critical to avoid lint yield reductions and quality penalties due to the narrow production window between planting and physiological maturity.

Texas A&M AgriLife Northern High Plains RACE trial data demonstrates that improved variety selection has the potential to increase lint value by $300 per acre. It is estimated that adoption of improved cotton varieties may contribute $75 million to regional farm profitability.

The bottom line

Bell said while some of the acreage growth in cotton could be due to the attractive price of cotton compared to grain, she attributes most of the acreage change to cotton’s need for less water and improvements in cotton technologies.

For many, it becomes a matter of managing irrigation at a deficit rate, which is not profitable with corn due to the reduction in crop productivity, she said. Consequently, farmers are diversifying their cropping systems to maximize farm productivity and profitability, and that will mean more cotton acres in the future.