Foods’ nutrient content from a one-second scan

Spectroscopy has a new use in food production, from the field to the grocery store

Texas A&M AgriLife Research scientists have demonstrated the first quick, accurate, not destructive, and portable way to scan produce for nutrient content. And, the same easy scan can identify diseases in living plants before symptoms appear.

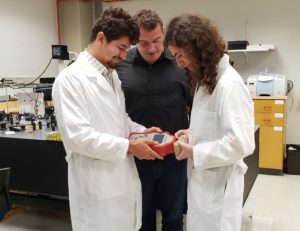

Dmitry Kurouski, Ph.D., assistant professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the Texas A&M University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, led the team in this new application of Raman spectroscopy. The results appeared in September in the chemistry journal ACS Omega.

A boost for farmers’ finances

“The method could someday be used to quickly estimate the economic value of grain in a field or grain elevator, or predict grain’s starch content,” Kurouski said. “This could change the economy for farmers and consumers.”

The results are “very impressive and open the path for field use in various agricultural applications,” said Torsten Frosch, Ph.D., an expert in spectroscopic sensors who was not involved in the study. Frosch leads the spectroscopic sensors group at Leibniz Institute of Photonic Technology, Abbe Center of Photonics, Friedrich Schiller University Jena in Germany.

Takes a second at the store

Raman spectroscopy measures how molecules scatter harmless laser light. A handheld scanner the size of a kitchen scale was used on six red or yellow corn kernels. Each scan took about a second. From the data, the team could calculate levels of nutrients inside each grain: protein, carbohydrates, fiber and carotenoids. Currently, analyzing nutrient content either destroys the sample or is less accurate or more time consuming than the team’s method. The team used the older methods to confirm the results.

“That’s huge,” Kurouski said. “When it comes to personal diet, if I have this technology then I can scan food that I consume, determining its nutrient value right on the spot.”

Saves time in fields, orchards

Next, the researchers used the same tool to identify corn plants growing in a field. Each plant’s signature pattern of light scattering allowed the team to identify different corn varieties, which would be helpful for both plant breeders and farmers. Corn was the country’s largest crop in 2019, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

And, food production is rife with other potential applications of the technique. For example, the team diagnosed citrus greening disease months before visible symptoms appeared. Raman spectroscopy detected telltale symptoms inside citrus plants. That study was published in Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry in May.

Solves a diagnosis problem

Talking to farmers gave Kurouski the idea to apply Raman spectroscopy in agriculture. Right now, two types of high-tech methods can identify a problem in a field of crops: satellite imaging and molecular biology. Both have serious drawbacks. Imaging is not specific enough — it might detect that crops are turning yellow but not the reason why. Molecular biology methods need experts to prepare samples. Getting enough samples tested can easily cost a farmer tens of thousands of dollars and take time. Because of the drawbacks, farmers tend to ignore these technologies, Kurouski said.

“From talking to farmers, I understood what they wanted. No sample preparation, quick turnaround, and at least 70%-80% accuracy,” Kurouski said. “I realized that Raman spectroscopy could fulfill all these requirements.”

The team now plans to work with partners to commercialize the technique. Then, it can truly become a useful tool for farmers, plant breeders and consumers.