Texas A&M helps prepare animal health ‘first responders’

Vaccine workshop leads veterinarians in foot-and-mouth disease planning

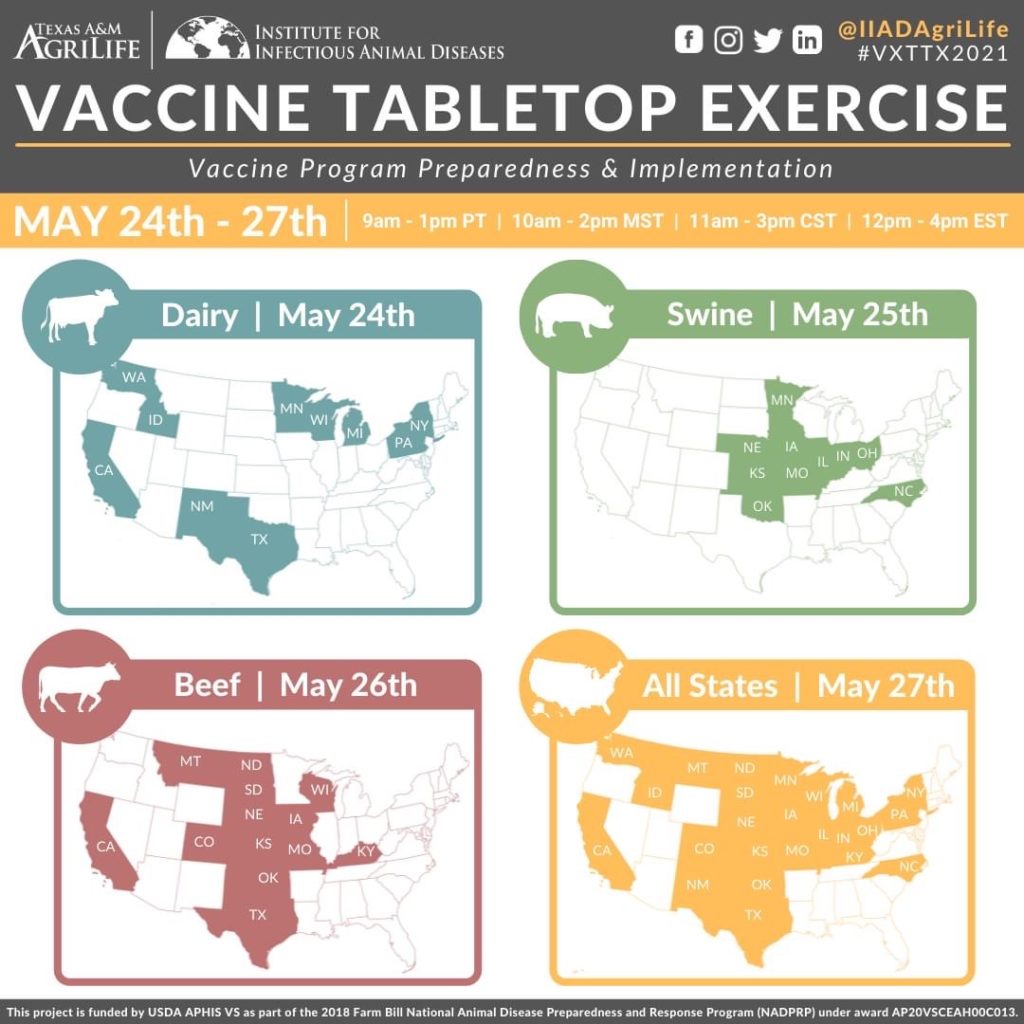

The Institute for Infectious Animal Diseases, IIAD, a unit of Texas A&M AgriLife, and Texas A&M University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, CVMBS, recently hosted a virtual foot-and-mouth disease, FMD, vaccine tabletop exercise.

The event helped animal health experts from top beef, dairy and swine states collaborate on vaccine plans for their respective states in the case of an FMD outbreak.

If FMD were to impact the U.S., it would be an economically devastating livestock disease. FMD does not affect human health nor food safety. However, it does hit the economy hard, costing billions of dollars in lost trade.

The U.S. has not had an outbreak of FMD since 1929. U.S. government agencies like the U.S. Department of Agriculture, USDA; Customs and Border Protection, CBP; and the Department of Homeland Security, DHS, as well as various Texas A&M University and Texas A&M AgriLife groups work every day to make sure it does not get back into the country.

If FMD does return to the U.S., events like IIAD and CVMBS’ vaccine exercise serve as “fire drills.” They help prepare key stakeholders like state and accredited veterinarians to stop the outbreak quickly and efficiently.

“Preparedness just makes you better able to respond when an event does happen,” said Susan Culp, DVM, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service veterinarian in the Department of Animal Science within the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and one of the event’s facilitators. She described veterinarians as the “first responders of animal health.”

“We’re like fire and EMTs; we have to do exercises and planning to be prepared in case we actually get into the real thing,” Culp said.

FMD and why it matters

FMD is a viral disease that infects livestock like cattle, pigs, sheep and goats. It also infects wildlife like deer, elk, bison and feral swine. It causes fever and painful sores in the mouths and on the tongues, feet and teats of infected animals, but it is usually nonlethal in adult animals.

The FMD virus does not infect humans. Despite the similarity in the name, FMD is not the same as the human viral disease called “hand, foot and mouth disease” that is common among young children.

FMD significantly reduces livestock’s productivity, making it an important economic threat. Compounding the economic threat of the disease, countries that are FMD-free go to extreme lengths to keep it out. This includes cutting off the trade of beef, dairy, pork and other livestock products with those countries that have it.

Glennon Mays, DVM, CVMBS clinical professor and one of the event’s facilitators, said it is important to raise public awareness of the disease. If an FMD outbreak were to occur in the U.S., there would be immediate trade repercussions.

“We expect we would be restricted from moving our livestock products into those channels of trade that we currently enjoy, as we have in previous situations refused to accept product from countries where foot-and-mouth disease has been diagnosed,” he said.

According to the U.S. Meat Export Federation and the U.S. Dairy Export Council, the U.S. exported $15.4 billion worth of beef, pork and lamb and $6.6 billion worth of dairy products in 2020 alone. This is only part of the value of exports from a single year that could be at risk if the U.S. were to have an FMD outbreak. Trade limitations due to the presence of FMD in a country can last years, if not decades.

The work to keep FMD out

The U.S. is listed by the World Organization for Animal Health as FMD free without vaccination. This is the highest level of safety relative to FMD. Many groups work to keep it that way.

“There’s interdiction at the borders, and there are early recognition programs,” explained Jimmy Tickel, DVM, IIAD veterinarian and one of IIAD’s developers of the event.

He gave the example of the Cross-Border Threat Screening and Supply Chain Defense program, CBTS, a DHS Center of Excellence led by Texas A&M AgriLife. CBTS, IIAD and CBP collaborate to create animal and plant disease training courses. They help personnel working on the borders recognize, manage and prevent dangerous pathogens like FMD from entering the U.S.

Accredited veterinarians are another layer of protection against foreign animal diseases.

“They are experienced in disease response and would likely be the first ones to be used in a foot-and-mouth disease or other foreign animal disease response affecting livestock,” said Brandon Dominguez, DVM, veterinarian with the Texas A&M’s Division of Research Global Health Research Complex and one of the event’s facilitators.

“Accredited veterinarians are the ones out there who really know where the farms are. They know who the farmers and ranchers are,” Dominguez said. “They have a better understanding of the movement of animals within their practice areas.”

Accredited veterinarians must undergo specific and ongoing training to maintain their accreditation. But the effort to train people to recognize FMD starts far earlier.

“From the veterinary education standpoint, we — and not just Texas A&M — teach and reinforce to our students the awareness of diseases like foot and mouth, what they need to do and who they need to contact if they ever encounter a situation in the field,” Mays said.

Vaccine role-play exercise to planning workshop

Originally, IIAD and the CVMBS’ event was designed as a two-day, in-person role-play exercise in College Station. Key representatives from the top six states for the beef, dairy and swine industries would be invited to play through their states’ vaccine rollout plans in hypothetical FMD outbreak scenarios.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the event to go virtual. This was a unique challenge since events like this require participant trust. Past, in-person events built trust through face-to-face conversation.

Sarah Caffey, program director at IIAD, oversaw the technical aspects of the workshop. She partnered with Daniel Foster, Ph.D., Global Teach Ag innovation specialist at Penn State, to create a discussion-friendly atmosphere using the Whova platform. The interactive features proved effective at fostering a trusting, collaborative experience for participants.

Going remote also allowed greater accessibility. Invitations expanded to the top 10 largest beef, dairy and swine production states. Since some states are in the top 10 for more than one industry, 24 states were represented.

“This was, to our knowledge, the first virtual workshop of its size involving 24 of the largest agricultural states in the nation,” Tickel said.

The fact that only three of the 24 states had an FMD vaccination plan also changed the event into a workshop instead of a tabletop exercise.

“A tabletop implies there are plans and all participants are in the same place in the planning process. That was not the case here,” Culp explained.

Despite the change in plans, it turned out better than expected.

“You had people from all across the spectrum of the planning process talking to each other, learning from each other, sharing with each other. To me, that was the best part of it,” Culp said.

Ultimately, the event was four days of directed discussion, strategic planning and the cross-pollination of ideas between the states on what needs to be involved with a FMD vaccination plan.

Planning to use the FMD vaccine

The FMD vaccine has existed since the 1960s. However, there have only recently been enough vaccines in the U.S. to make vaccination a practical strategy in the event of an outbreak.

Tickel and Dominguez explained that the 2018 Farm Bill supplied more funding for FMD vaccines. This included opening up a second vaccine bank for U.S. use alone. The U.S. shares the older vaccine bank with Canada and Mexico.

“With more vaccines available and the ability to produce much more rapidly, vaccine is now a viable option on the table as a tool that could be used in a national outbreak situation,” Tickel said.

“We would be able to protect more of our animals,” Dominguez said. “But with the number of livestock that we have now, it still exceeds the amount of vaccine initially available, so the approach has to be strategic.”

According to the USDA, there were an estimated 93.6 million head of cattle and 7.75 million head of sheep and goats as of January and 74.8 million head of swine as of March. That’s almost 200 million head of livestock that could be susceptible in the case of an FMD outbreak.

Much like with the COVID-19 vaccine, where the limited supply went to at-risk people first, the distribution of the FMD vaccine would have to be prioritized in the case of an outbreak. Tickel noted the recent experience of the national COVID-19 vaccine rollout was discussed widely at the vaccine exercise.

“This planning effort was fascinating because the resource became available in the amounts that made it valuable,” he said. “But also, given the COVID experience, there was an awful lot of attention on what a vaccine can and cannot do and what can go right and what can go wrong with a national rollout.”

Challenges in the vaccine planning process

The vaccine exercise was part of preparing animal health “first responders” to incorporate FMD vaccination into their states’ animal health plans.

“All states have plans for foreign animal diseases, including FMD,” said Culp. “It’s the vaccine component to the planning that made this a brand new discussion.”

Over the course of the event, participants identified several challenges their states might face in an FMD outbreak. However, the complexities of managing a national vaccine distribution program to fight an outbreak of the most contagious livestock virus on the planet and having states work together on behalf of their livestock industries was the overarching challenge of the workshop.

Tickel explained that, in the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, public health officials at every level of the vaccine distribution helped get vaccines from the national stockpile into individual arms.

“For animals, there are no government officials to oversight such programs on the local level,” he said. “That occurs through accredited veterinarians, who are private practitioners. A state veterinarian would actually have to contract private practitioners and work them in a public capacity to oversight the FMD vaccine program.”

Most representatives at the vaccine exercise concluded that their states do not have the trained personnel necessary for a vaccination plan. Mays summarized the issue as being “lots of hats that need to be worn and not enough heads to wear them.”

Other challenges identified at the exercise included cold chain security issues — making sure states can keep vaccines cold at every step in the process — and vaccination record keeping.

“The complexity involved is why we need to have workshops where we can discuss the challenges at hand and project out additional challenges and things that could happen,” Tickel said.

A community of collaboration on animal health

The vaccine planning exercise also created an opportunity for states to collaborate on their FMD vaccine plan development. The project coordinators said this collaboration was one of the best outcomes of the event.

“Nobody has all the answers. Some states have worked through some parts of it, and others have figured out other parts,” Dominguez said. “Together, they might be able to figure out some of the other problems that they see coming.”

Culp said it also gave participants tangible ideas of what they can do in their state’s planning process.

“It allowed the states to identify some key gaps, and I think that they probably walked away knowing what they could prioritize and get done now,” she said.

Tickel described the event as developing a community of subject matter experts who can represent their states going forward in the planning process.

“Our event brought together state players so they could collaborate on those efforts and build all plans with one perspective and raise all boats with one tide,” he said.