Barbed wire collection preserves range history

Collection shows evolution of rangeland, ranching management

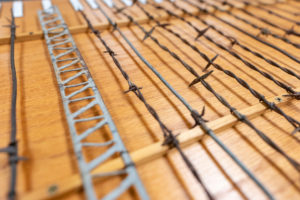

The halls inside Texas A&M University’s Department of Rangeland, Wildlife and Fisheries Management are being adorned with displays showcasing historical strands of barbed wire meant to connect resource stewardship’s past, present and future.

Roel Lopez, Ph.D., Department of Rangeland, Wildlife and Fisheries Management head in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, commissioned the installation of a donated barbed wire collection displayed in a series of panels.

The display panels feature hundreds of strands of barbed wire that recall the evolution of fencing in Texas and around the country as far back as the mid-1800s.

Lopez said the collection is a reminder of the history that shaped how natural resources were managed and how the department can guide future land and resource stewardship.

“There is a connection with the department’s mission to promote stewardship for private lands, natural resources, and wildlife and fisheries populations,” he said. “It is a reminder of the history that brought us to this point, but also that the people who walk these halls have an opportunity and responsibility to improve our future stewardship methods and approaches.”

The collection and connection

Gaylon Lane, a soil scientist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resource and Conservation Service, NRCS, donated the panels to the department 20 years ago. Lane worked for NRCS for 35 years and began collecting barbed wire in 1965.

The oldest piece of wire in Lane’s collection dates to 1853 – a smooth, single-wire snake-ribbon pattern called the “Meriwether.” Pieces in the collection show how fencing wire designs changed from single, smooth wire to multiple-strand mesh and braided wire with various fixed and mechanical barbs. Each strand is marked with its creator, patent name and date.

The panels have been in storage since the department’s home has undergone renovations and name changes over the past few years.

Wayne Hamilton, former director of the Center for Grazing Lands and Ranch Management at Texas A&M, said barbed wire received mixed reviews when first introduced to open ranges in Texas in the mid-1800s.

Before barbed wire, cattle identified by their outfit’s brand often crossed property lines to consume rangeland, pasture and water. Barbed wire helped keep cattle in, but just as important to ranchers, it kept other cattle out.

Hamilton noted an article written in Zavala County in the 1870s regarding local reactions to barbed wire.

“When the first barbed wire came into that part of the country, some people didn’t like it a little bit and immediately proceeded to cut it,” he said. “Some trouble ensued, but, over time, it settled and became accepted that there was not going to be any more free and open range.”

“Barbed wire changed the whole aspect of grazing livestock on western rangeland,” Hamilton said.

Department ready to guide future land stewardship

The expanded use of barbed wire represents a major shift that impacted how private lands and natural resources were managed.

Lopez said he hopes the historical displays are a visual reminder to students and faculty that the department will shape the future of rangeland and resource management.

“When we thought about the caliber of education we wanted to offer, our vision started with our students—the next generation of field experts, lifelong learners and professionals who will work at the nexus of research and Extension in rangeland grazing, land stewardship, aquaculture and wildlife management,” Lopez said. “There is a strong interest and need to be relevant to our students and those we serve and relevant in impact as we advance stewardship of natural resources.”

Providing the next generation of experts is a critical mission, Lopez said, because land stewardship has broad economic, social and environmental implications for Texas, the nation and the world.

Providing stewardship guidance will continue to be a challenge amid increased land-use changes, fragmentation and generational shifts in landowner expectations and goals, Lopez said.

“There are implications and challenges related to the expectation that Texas’ population will double over the next several decades,” he said. “Land stewardship becomes more and more important across generations as it relates to the land itself but also other natural resources from wildlife to water.”