Retiring from a lifetime of plant pathology research

AgriLife Research’s Rush provided solutions to address grower concerns

Thirty-five years ago, Charlie Rush, Ph.D., was recruited to start a plant pathology program in Amarillo for Texas A&M AgriLife Research. He initiated research critically important not only to the Texas Panhandle and the state of Texas, but also of importance nationally and internationally.

Now, after a career spanning more than 47 years, Rush will retire.

“I still love doing this work,” he said. “It has been an amazing opportunity for someone who loves science and has an imagination. I’ve been able to do almost everything I had the ideas to do.”

A Regents Fellow of Plant Pathology and Senior Faculty Fellow in Texas A&M’s Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, Rush has conducted the applied research needed to provide practical solutions to address the concerns of Texas farmers and threats to U.S. agriculture.

He moved to Amarillo in 1986 from Washington State to study economically damaging diseases of crops produced in the Texas Panhandle. His early focus was sugar beet diseases, so he worked with the farmers who supplied beets to the local Holly Sugar factory.

“When I first came here, there was no lab, no greenhouse space, and no supplies or equipment for my program,” Rush said. “But over the years, I’ve been able to build the program, and gaining the trust of Texas growers during the process has been very rewarding.”

His research has covered most major crops and has extended into several projects on biotic and abiotic factors that impact the quality and yield of locally grown vegetables and specialty crops.

“From the moment I met Charlie 13 years ago, he consistently impressed me by his creativity, his ability to link seemingly unrelated observations into cohesive testable hypotheses, and his incredible organizational talent,” said Leland “Sandy” Pierson, Ph.D., professor and head of the Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, Bryan-College Station. “Charlie makes everyone around him a better scientist and a better person, which is the true essence of leadership.”

Building a life as a researcher

Rush first started with Texas A&M University as a graduate teaching assistant in 1974 and then spent two years as a technician, followed by a stint as a graduate research assistant and Plant Pathology Laboratory coordinator at College Station.

In 1981, he took a post-doctorate research scientist position at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center in Temple. He spent three years there building his skills before taking a research scientist position with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service in Prosser, Washington, in 1984.

Initially, Rush said, what he lacked in experience was counterbalanced with his enthusiastic passion for science. His competitive nature and love of words fueled his writing. Hundreds of successful grant proposals helped fund research projects, equip three labs, build two greenhouses and six high tunnels, acquire a site-specific variable rate center pivot, and hire staff to grow his program.

Over his career, Rush was the primary investigator, PI, or co-PI responsible for bringing in over $19 million in research funding grants. He also was the senior author or co-author of approximately 150 referred journal articles.

Developing a plant disease diagnostic service

Throughout his career, Rush said he has tried to be early on the scene and early with solutions regardless of the crop or specific pathogen or disease problem. His research on rhizomania of sugar beet, wheat streak mosaic and zebra chip of potato has significantly impacted both the direction of research and how farmers manage these diseases.

Rush built his program researching soilborne fungal pathogens and plant pathogens with arthropod vectors. Initially, he worked on beet necrotic yellow vein virus, a new disease in Texas and the U.S., which caused rhizomania of sugar beet. He studied the interactions between irrigation frequency and duration on disease incidence and severity. Based on his work, recommendations were made to revise current irrigation scheduling practices.

When the sugar plant closed, Rush’s experience was still called upon by beet industry leaders around the country. He was invited to join the International Working Group on Plant Viruses with Fungal Vectors. This major area of work, he said, created a source of funding and a lot of opportunities.

When sorghum ergot first entered the state, Rush and his research team worked closely with the Texas Seed Sorghum industry to develop a disease forecasting model based on climatic conditions identified by Doppler radar.

“Karnal bunt was another new disease to Texas and the U.S.,” Rush said. His team accepted the challenge to do something about it. “It was devastating to growers because, due to the politics, if it was detected on a farm, the entire farm and immediately surrounding farms were quarantined.”

When karnal bunt was first detected, he established a diagnostic lab to identify the pathogen and provide farmers with the documentation needed to certify a “disease-free crop” so it could be sold. He conducted research on pathogen distribution and potential for spread, which resulted in several publications used by U.S. Department of Agriculture-Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service to develop a Pest Risk Assessment and ultimately to help provide the documentation necessary to deregulate quarantined farms.

Rush’s team discovered that wheat streak mosaic, WSM, not only affects grain yield and quality, but also reduces root function and crop water-use efficiency. They educated farmers that the addition of fertilizer or irrigation water to severely diseased wheat was a waste of labor, energy and natural resources.

Most importantly, Rush discovered that disease tolerance of the TAM 112 wheat variety is primarily due to resistance to the wheat curl mite vector. This finding provided vital information to geneticists and breeders in their efforts to identify and deploy genetic resistance to WSM and other mite-vectored viruses.

Rush’s broad experience working with a number of plant pathogens, including viral pathogens that required molecular techniques to detect and study, resulted in him being asked to set up a branch of the Great Plains Diagnostic Network in Amarillo. Later, the expertise he and his team were able to develop opened the doors to his work with zebra chip of the potato.

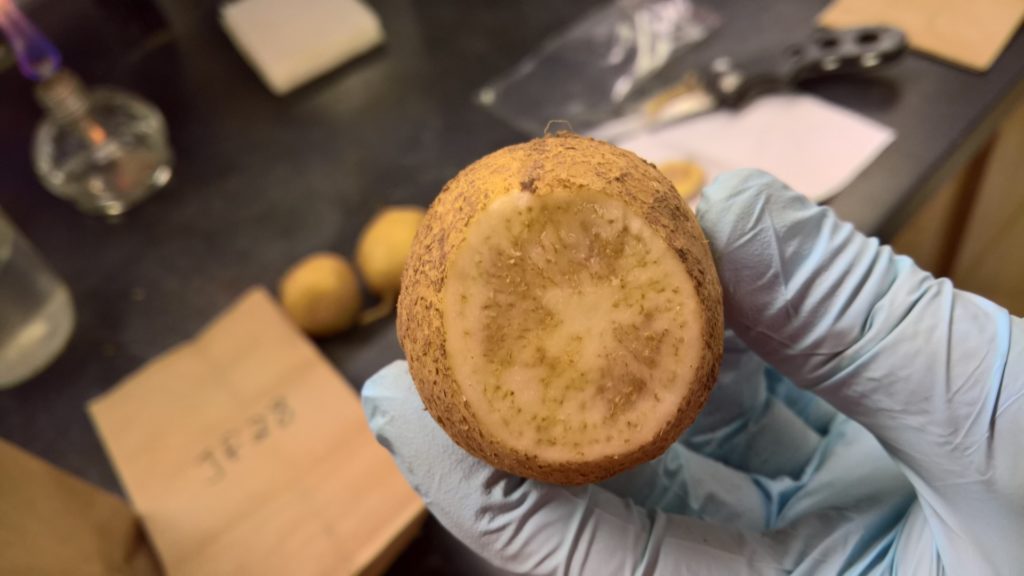

Zebra chip was another new disease to Texas and the U.S., and when it first came to Texas, it almost wiped out the fledgling potato industry. As losses to the disease increased statewide, the Texas Department of Agriculture approved funding for research on the disease that was threatening the industry’s survival. Then, in 2010, Rush garnered a $6.7 million USDA-National Institute of Food and Agriculture grant with matching funding from growers throughout Texas and across the country.

He served as national program director for the Zebra Chip Specialty Crop Research Initiative for five years, coordinating a team of 30 scientists representing seven universities and USDA-ARS. The team’s research on the zebra chip pathogen and discovery of the potato psyllid as the vector helped the industry begin to manage the disease and vector. The team was awarded the NIFA Partnership Award for Mission Integration of Research, Education and Extension by the USDA in Washington in 2014.

Specialty crop research starts as hobby

Rush said his love of gardening took him to his latest research chapter, where he developed a program for growing vegetables both in fields and under high tunnels. Additionally, he has worked with growing a number of specialty crops under high tunnels.

For many years, Kevin Crosby, Ph.D., an AgriLife Research vegetable breeder, needed a northern location to test his vegetable breeds, and Rush agreed to watch over them in the Panhandle.

“We started noticing one of the main problems with growing tomatoes in this region was tomato spotted wilt, so Crosby began breeding resistant varieties,” Rush said. “Just this spring, we discovered that everything in the region is a resistance-breaking strain of the tomato spotted wilt virus, not only on tomatoes, but also on peppers as well.”

Now, with the help of the Texas A&M AgriLife Insect Vector Seed Grant Program, a team including plant pathologists, molecular virologists, vegetable breeders, entomologists and plant disease epidemiologists has been established to study this disease and develop environmentally and economically sustainable management practices.

Teamwork develops future researchers

Teamwork and getting to spend time with people who love what they do has been a key to his success, Rush said. Although he has made hundreds of presentations for scientific meetings, agricultural industry, commodity organizations and grower groups in Texas, nationally and internationally, he said, “I couldn’t have been as productive and successful without my team.”

While many members have come and gone, he said his core crew — Fekede Workneh, Ph.D., plant disease epidemiologist; Jewel Arthur, greenhouse manager; and Li Paetzold, molecular plant disease lab manager — have been in his program for approximately 15 to 20 years.

Along with those in his current Amarillo program, who will continue the research, Rush takes extreme pride in the many technicians and undergraduate, graduate and post-doctoral students he has trained who have gone on to lead their own research programs.

“The true test of a scholar is the extent to which he reproduces after his own kind,” said Brent Auvermann, Ph.D., professor and center director, Texas A&M AgriLife Research, Amarillo. “Charlie’s legacy here is defined in large measure by the skills, creativity, growth and reputation of the staff he has trained over the years. I’m not sure how we replace that.”

Honors and accolades

Rush has received numerous honors, recognitions and awards. Since 1975, he has been an active member of the American Phytopathological Society, APS, providing committee leadership and serving as a senior editor for both Plant Disease and Phytopathology journals. He was honored in 2008 to be named a Fellow of the American Phytopathological Society.

Despite earning prestigious awards and having opportunities to make influential impacts in his field, Rush said what he values most is the people who have guided and supported him as well as those he has been honored to encourage and mentor.