Remote monitoring helps find solutions to crapemyrtle bark scale

Insect already spread to 17 U.S. states, threatening million-dollar crapemyrtle industry

A collaborative team of researchers in the Texas A&M College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Department of Horticultural Sciences and the Department of Biology has developed a unique system of identifying host plants of crapemyrtle bark scale, an insect that destroys plants by feeding on their sap.

The crapemyrtle bark scale insect has spread to 17 states in less than two decades and poses a significant threat to the green industry by spreading a disease of the same name.

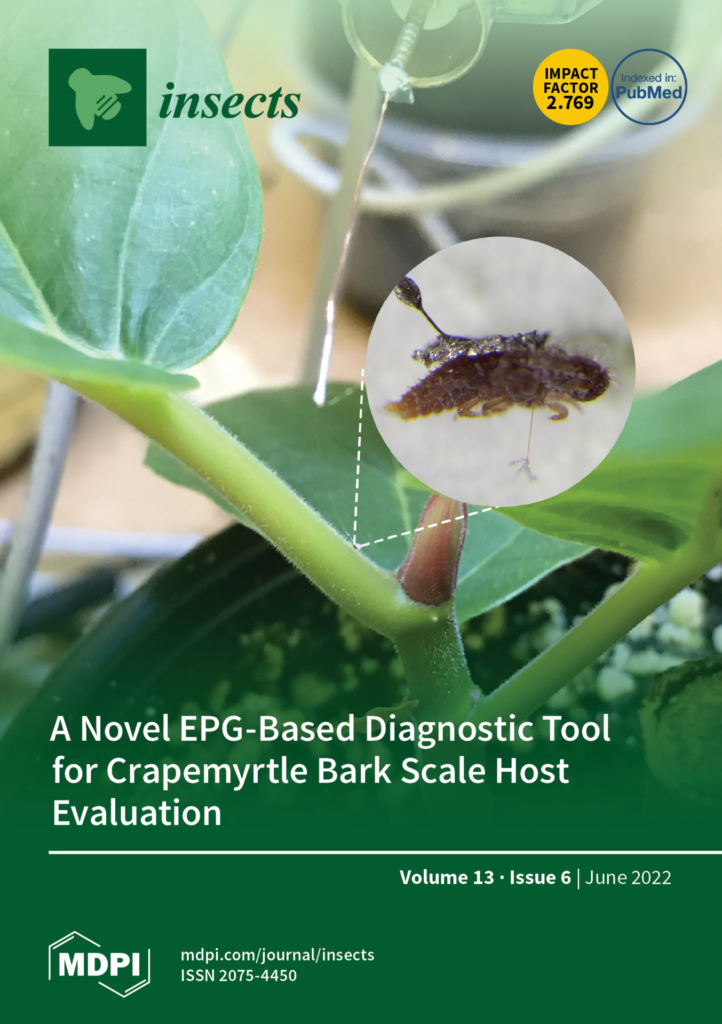

A unique monitoring system using electrical penetration graph, EPG, and custom software has allowed the team to virtually eliminate the need for intensive greenhouse studies and costly labor. The study was recently published in the scientific journal Insects.

The work has captured the interest of green industry representatives seeking a way to thwart the insect’s namesake disease, which has cut the crapemyrtle market in half. Crapemyrtle sales have an annual economic value of $69.5 million, according to the researchers.

“It’s imperative to control this pest because it can spread quickly and potentially threaten the green industry and ecosystem,” said Bin Wu, Ph.D., who recently graduated from the horticultural sciences program and was lead author of the study.

The research team involves a collaboration between the research groups of Hongming Qin, Ph.D., associate professor of biology, and Mengmeng Gu, Ph.D., formerly with the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service. They co-advised horticulture researchers Wu and Runshi Xie, Ph.D., also a recent graduate. Elizabeth Chun, undergraduate researcher in the Texas A&M Department of Biology, and Gary Knox, Ph.D., environmental horticulture and nursery crops Extension specialist with the University of Florida, round out the team.

The crapemyrtle bark scale insect is crafty. It has long mouthparts that penetrate into crevices of the crapemyrtle bark and has a wax covering on its back that allows it to dodge insecticides that are sprayed on tree bark. Meanwhile, it continues to suck sap from the plant, robbing critical nutrients needed for plant growth.

From Chicago Hardy figs to soybean, the pest seeks a wide range of hosts, further heightening the need for a cure. “Our research is to figure out the host range, or what kind of plant species besides crapemyrtle are exposed to this,” Wu said.

Eliminating expensive labor

The research began in 2019, when the team began testing different crapemyrtle species in a greenhouse for their susceptibility. The initial tests used manual labor and took more than half a year. That’s when the team determined a more efficient and real-time method was needed.

Using the EPG monitoring system, the team was able to track the probing activities of the insect in the plant. The results helped the researchers learn more about the interaction between the insect and plant and gain a better understanding about potential pest control. The EPG waveforms allowed the researchers to observe what nutrients the crapemyrtle bark scale insect extracts from the plant.

“Through those observations and determining what nutrients were being taken away, we were able to consider which were most likely host plants,” Wu said.

Some crapemyrtle bark scale insects were able to drink water but not able to drink other nutrients to support their growth and development. The plants these insects were found on were considered “potential plants,” meaning the bark scale could survive for a while and potentially break down the plant defense to force the plants as hosts.

Using EPG and the software system developed by Chun, the team was able to calculate the frequency and relative amplitude for each EPG waveform from the over 500 megabytes of raw data in a few seconds. Studying the insect behavior gives researchers a clearer understanding of potential plants and attraction.

“We needed a way to annotate that data and Elizabeth Chun came into the project conducting the programming,” Wu said. “We worked together to figure out the coding work to make the computer know how to extract the EPG waveforms, what they look like, the duration of the waveform, etc. using this software. There are both online and downloadable versions. If someone doesn’t want to download online, they can click the link to use the online version.”

The software is open source. The project has already been presented at several academic professional meetings including the American Society for Horticulture Science, the International Propagators Society and the Lone Star Horticulture Forum.

After presenting at the Lone Star forum in January, an industry meeting, Wu said some green industry representatives said they would be able to collaborate to test their plants.

“They showed their interest and that’s why we didn’t apply for patent, we wanted to share with academia, the public and industry,” he said.

Next steps

The research team is considered early pioneers in the crapemyrtle bark scale research. Xie has been working in insect biology on a project called Life Table, an ecological tool for studying different organisms’ development and population dynamic, which has not been done for the bark scale previously. This has led to many important discoveries, such as the insect’s mating behavior.

Xie said scale insects are interesting species with diverse genetic systems, and some of them reproduce asexually.

“The female leads a very sedentary lifestyle,” Xie said. “They are pretty much waiting on the male, which is a fly, to instigate mating behavior. For the male to find a female, the female must release a sex pheromone. Our next research project will seek out what compounds are released, and how to use them to disrupt mating.

“Right now, the control of this insect is the use of systemic pesticides. But the insects are protected by scale covering, which makes spraying ineffective. To treat chemically, we need to drench the soil to deliver the chemicals into plants, and insects feeding on the sap will die. However, this practice is also detrimental to pollinators. Our focus will be to see if we can come up with novel systems that control insects without relying too much on pesticides.”

Wu added that work includes trapping the male insects to disrupt mating behavior.

“We also want to pursue a cultivar resistant to crapemyrtle bark scale,” Wu said. “Currently, I’m looking into developing resistant, novel cultivars and working with industry. They are a bridge for us to learn what their priority needs are.”