Texas timber finding added value in new markets

Texas Crop and Weather Report – Aug. 8, 2023

The Texas timber sector has experienced ebbs and flows of supply and demand and other market forces, but new products and opportunities are adding value to trees, said a Texas A&M Forest Service expert.

Fiber grown, managed, harvested, processed and manufactured around the state continues to play a big role in Texas’ economy with a total impact of around $41 billion, and the industry supports more than 172,000 jobs each year, said Eric Taylor, Ph.D., Texas A&M Forest Service silviculturist, Overton. The value of harvested timber consistently ranks seventh as an agricultural commodity for Texas.

Much of the traditional Texas timber industry is located within 43 counties of East Texas. Timber tracts make up around 11.5 million acres of those counties’ nearly 22 million acres, Taylor said.

Texas timber is turned into products ranging from two-by-fours and plywood for home construction to cardboard for boxes, wood for furniture and home furnishings and mass timber for large structural supports.

Texas sawmills produced more than 1.5 billion board feet of lumber in 2022. With each board foot amounting to 12 inches by 12 inches by 1-inch thick, that is enough board feet for typical framing studs to reach the moon and back to Earth. More than 3.1 billion square feet of structural panels, like oriented strand board or plywood and T1-11 siding, was also manufactured from trees harvested in Texas.

There is also an increasing amount of niche-market timber products from Central and West Texas, where, for example, large specimens of native species like mesquite and live oaks are harvested for products like live-edge tables or countertops and command high prices.

“The Texas timber industry has softened in some ways and strengthened in others,” Taylor said. “Some things changed, and some things will likely never change. Timber is still heavily tied to lumber and housing starts, but other products are different. A large pine tree might be worth only $70 to a landowner on the stump while a live-edge slab from a hardwood tree from Central Texas could be worth thousands of dollars.”

New value for Texas timber

The traditional timber market — pulpwood and lumber — is relatively soft for landowners despite relatively high prices at retail stores, Taylor said. Retail lumber prices have softened somewhat since prices skyrocketed during and after the pandemic led to production slowdowns and an uptick in at-home renovations.

But the industry’s efficiency at harvesting and replanting timber tracts fills the demand for pulpwood when acres are thinned once or twice starting at around year 15 to make way for lumber-bound pines to reach maturity at around 28-years old, he said.

Taylor is a proponent of lower initial planting densities, around 500 seedlings per acre, but 900 pine seedlings or more might be planted per acre at the start. Crowding pushes trees to grow straight and tall but they become stressed around 15 years of age. At that time trees are thinned to allow them more access to sun, soil nutrients and water to stay healthy as they grow toward maturity.

The forecast for traditional timber products is positive because of Texas’ relatively strong housing market. Taylor said housing starts were improving and higher than the previous reporting period with around 1,300 new residents estimated to be moving into the state daily.

Exports of lumber, especially to Mexico, continue to be strong as well, he said.

Taylor said traditional products like printing/copy paper are no longer made in Texas, but that the “Amazon-effect” has strengthened the demand for other products like paperboard and cardboard for shipping boxes. Around 2.5 million tons of paper-based container board were manufactured in Texas last year.

“When you buy something from Amazon, those items come in a box, and that box is made out of paperboard,” he said. “Often times even little items come in big boxes. That’s part of the industry that Texas timber has captured.”

New products add value

Cross-laminated mass timbers are another promising new product adding value to trees, Taylor said. Mass timbers are super-strong constructed support beams that are being adopted by architects and engineers in high-rise buildings and commercial structures because of the aesthetic and environmental benefits over other building materials.

Carbon sequestration is another boon for timber landowners, Taylor said.

As larger companies attempt to reduce their carbon footprint, they purchase carbon credits to offset their carbon emissions into the atmosphere. These credits come from working forest lands that are capturing carbon from the atmosphere and storing it as wood.

Carbon sequestration agreements help incentivize proper tending of forests, which might mean removing some trees so others can thrive, conducting prescribed burns to reduce fuels that could lead to wildfire, and controlling invasive, unwanted and/or competing vegetation, Taylor said. Healthier forests pull more carbon out of the atmosphere over the long-term and make more long-lived products than do unhealthy forests.

Sequestering carbon adds value on the front end of the timber cycle, but whether the products are short-lived items like paper or long-lived products like two-by-fours also counts.

“Now there is value added to the entire life of the forest from carbon and pulpwood from management to the end product,” Taylor said.

New opportunities for new landowners

How timber is valued is changing how timber is managed, but population growth is changing how timber will be grown.

Around 5.1 million East Texans own 50 acres or less, and continued land parcellation is shrinking the average size of working forests, Taylor said. Parcellation into smaller and smaller land holdings can impact a tract’s timber management future. Timber harvesters prefer to clear large tracts because of the costs associated with setting up before and packing up after harvest.

The Texas A&M Forest Service is working with landowners in these smaller tracts to overcome these “economy of scale” limitations and combine smaller tracts into a larger aggregate tract that is managed in unison, he said.

Taylor said better management results in healthier forests and more vigorous trees that can handle stressors like drought and be less susceptible to disease and pests like boring beetles. Drought and competition with too many trees and understory can stress mismanaged timber tracts, which opens the door for bark beetles or wildfire to finish the job.

Carbon sequestration and better harvest values are good incentives for neighbors to work together, he said.

“The economy of scale works against landowners with smaller tracts because it generally takes 100 acres to attract contractors to do the work,” he said. “Pooling together makes a larger neighborhood tract more attractive.

“We are working to educate landowners about their options and help them navigate the changes within the industry. A lot of these changes add value, landowners just need to know their options.”

Go to https://texasforestinfo.tamu.edu for numerous applications related to forest management including My Land Management Connector to connect with neighbors, service providers and Texas A&M Forest Service experts.

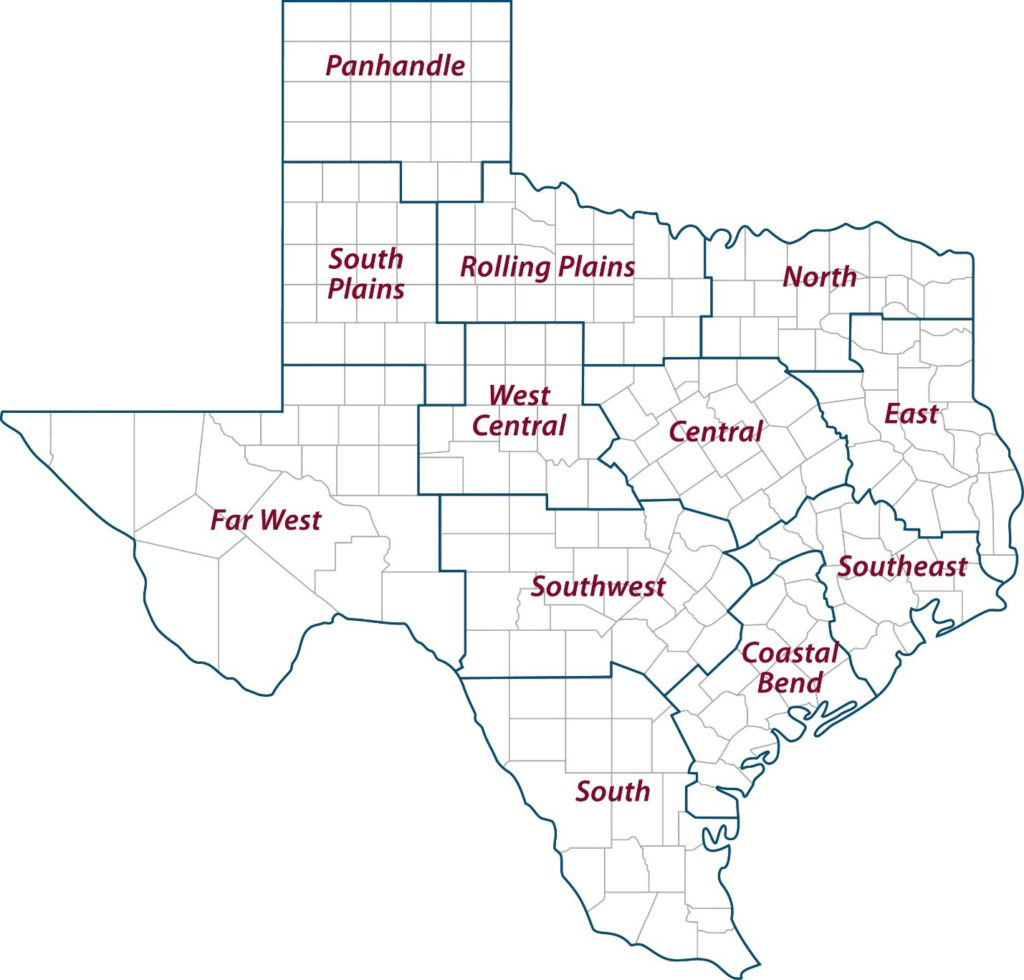

Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service district reporters compiled the following summaries:

CENTRAL

The reporting period marked the end of the hottest July on record. Intense heat and dry weather persisted with daily temperatures reaching 100-112 degrees. Nighttime lows only dropped into the upper 80s. Water restrictions were being enforced, and intermittent fires had broken out. Pastures were showing drought stress, and soil moisture was continually decreasing. Stock tanks were drying up and lake water levels were extremely low. Trees were being affected by the heat and lack of water. Pecan producers and other irrigators were anticipating a loss of water access in mid-August. Corn harvest yields ranged between 60-160 bushels per acre and were still expected to be above the long-term average of 75 bushels per acre. Sporadic yields were linked to the planting date with mid-April planting yields slightly below average. The sorghum grain yield was expected to be lower than anticipated, but the forage yields were decent. Sorghum grain yields ranged from 2,000-6,000 pounds per acre. Cotton bolls opened, but the crop needed rain to be saved. There was a lack of forage grasses available and only one hay cutting was made. Pastures were grazed down, brown and dormant. Cattle were being supplemented. Ranchers were selling off calves due to the hay shortage. Deeper culling of livestock was expected. AgriLife Extension agents were receiving calls regarding crickets, grasshoppers and blister beetles.

ROLLING PLAINS

The week was very hot and dry. All counties reported pastures and summer forages showing stress and drying up. Many ranchers were supplementing their cattle with hay due to the lack of available forage for grazing. Stock tanks and ponds were extremely low or completely dry, leading to an increasing concern for water availability for livestock. Cotton crops without irrigation were burning up due to the lack of rain and extreme heat.

COASTAL BEND

Hot and dry weather continued to cause soil moisture and agricultural conditions to decline. Cotton harvest started with early plantings yielding better than later planted fields, which struggled with continued heat and lack of rain. Corn harvest was winding down. Rice was being harvested and crop residue was being baled for hay to help offset shortage. Grain sorghum harvest is almost complete with average to above-average yields reported. Pecan trees were dropping nuts due to dry conditions. Rangeland and pasture conditions were extremely dry. Some hay was being cut, but hay supplies were short, and many ponds were dry. Livestock held their condition, with inventory numbers dropping slightly. Some producers started early weaning.

EAST

Drought conditions increased across the district. Burn bans popped up in several counties. Soil moisture levels continued to decrease. Pasture and rangeland conditions were fair to poor. Subsoil conditions were short, while topsoil conditions were very short to short. Hay production was at a standstill in most areas. Hay prices began to go up despite quality or bale size. Producers in some areas were supplementing livestock with hay or grain. Livestock were in fair to good condition. Extreme heat has ponds and creeks drying up at an accelerated rate. Harrison County received reports of dead fish in ponds due to low-dissolved oxygen levels. Houston County reported issues with walnut caterpillars. Wild pigs remained a problem causing damage to pastures and hay meadows.

SOUTH PLAINS

Conditions were very hot and dry. Some scattered showers helped retain the little moisture in the soil. Farmers continued to irrigate after water was not needed for much of the season. Continuous excessive heat and wind with no rain were beginning to burn up rangeland and take a toll on the crops. Cotton, corn and sorghum conditions varied from poor to fair. Pumpkins started setting fruit. Cattle were in good condition with very few producers providing supplemental feed in some areas. In other areas, livestock looked good, but ranchers were supplemental feeding with hay.

PANHANDLE

Conditions were very hot and dry with temperatures reaching 100-plus degrees. Most counties reported adequate to short subsoil and topsoil moisture. Tillage and spraying continued on fields to be planted in wheat and fallow fields that were just harvested from wheat. Corn and sorghum were stressed by the hot, dry, windy weather. Irrigated corn looked good. Many late-planted corn fields were in pollination phase, and time will tell if the heat has a negative effect. Pastures and rangeland were starting to go dormant, and weeds were prevalent in many ranch pastures. The majority of ranch pastures were not restocked. Pasture and rangeland conditions were poor to fair overall. Overall, crops were in good to fair condition.

NORTH

Subsoil and topsoil moisture were short to adequate for most of the counties. Temperatures remained extremely high and dry. The heat was stressing plants. Pasture and rangeland conditions were fair to good for most counties, but a few reported very poor conditions. Summer grasses were dying and burn bans were being implemented. Corn, soybean and sorghum harvests continued, and yields were very high. Grasshopper populations were extremely high and increasing. Bermuda grass and other forages were still growing well with deeper soil moisture. Hay baling was going at full speed. Nuisance flies were high in cattle. Livestock conditions were good and continued to improve.

FAR WEST

Daytime temperatures were in the upper 90s and low 100s with overnight temperatures in the 70s. There were a few sporadic rain showers in different areas of the district that left trace amounts of moisture. The Davis Mountains received widespread rainfall and cooler temperatures. Producers were hoping the weather indicated the start of the monsoon season and more consistent rainfall. The district was in desperate need of rain to improve soil moisture, cotton, hay and rangeland conditions. Dryland cotton was nearing cutout. Cotton was starting to shed more squares and small bolls. Insurance adjusters were looking at more cotton fields and removing fields that will not be harvested. A little corn was harvested, and yields were better than expected. Sorghum was mature and should be harvested soon, and most fields looked good. Melons continued to be picked and were doing well despite the heat. Pastures were in terrible shape. Weeds were prevalent in low spots and in livestock tanks that were drying down. Livestock were in fair condition, but forage was becoming limited. Most pastures were completely bare, and cattle were being supplemented with cake and feed. Feral hogs were an issue. Despite dry conditions the mourning dove population was moving into the district.

WEST CENTRAL

Hot, dry conditions persisted with temperature highs over 100-degrees daily. All areas needed rainfall. Water levels were dropping in tanks and lakes. Some field preparation was made for small grains planting. Producers cut and baled some hay, but most forages were drying up and going dormant. Corn and sorghum harvest was wrapping up with average yields reported. Grain sorghum yields were around 1,000 pounds per acre in some areas. Remaining corn fields were struggling in the heat. Cotton was suffering and many fields may not make it to harvest. Grasshoppers continued to be a problem. Stressed pecan trees were dropping immature pecans. Conditions were causing wildfire concerns. Pastures needed rainfall badly, but rangeland conditions were holding. Hay was being put out for livestock due to the lack of grazing in some areas. Some areas had fair amounts of forage remaining, but conditions were not improving. Ranchers were culling herds. Cattle prices were $3-$6 higher per hundredweight at local sale barns.

SOUTHEAST

Conditions were hot and extremely dry. Soil moisture conditions were very short to adequate. Daily temperatures were around 100 degrees. Grass and trees were struggling. Heat and lack of rain were taking a toll on hay production. Pond levels were decreasing rapidly. Producers were feeding hay due to the lack of grazing. Rangeland and pasture ratings were very poor to fair. Irrigated hay fields were receiving water. Corn, sorghum and rice were being harvested. Cotton was maturing. Later-planted rice fields continued to progress, and some early season rice was being flooded for ratoon. Grasshoppers were prevalent.

SOUTHWEST

Extremely hot and dry conditions continued, and soil moisture levels were declining. Record high temperatures and no rain were in the forecast. Crops and pastures continued to show signs of stress. Cotton was in bad shape. Forage sorghum, grain sorghum and corn harvests were in full swing with average to above average yields reported. Corn harvest was near completion. Some producers baled green sorghum stubble. Most producers made one hay cutting. Pastures continued to decline. Rangelands were very dry and burn bans were being reinstated. Pond and stock tank water was declining and getting critically low in some areas. Las Moras Springs located in Kinney County stopped flowing. Producers were providing supplemental feed to livestock, which were in fair condition. Producers started weaning calves and continued to cull herds. Cattle markets were high, and the sheep and goat markets improved from the previous weeks. Large numbers of cows were going to auction. Wildlife were doing well, but water supplies were dwindling and there were increased reports of algae blooms and worsening water conditions. There were reports of fish dying from low-dissolved oxygen in ponds.

SOUTH

Excessive heat and drought continued. Fieldwork continued for strawberries. Corn harvest was in full swing with about 85% of fields already harvested. Irrigated cotton crops continued to stress due to extreme heat, but harvest was underway in some areas. Peanut fields were continuing to develop under irrigation and were in the pegging stage. Pasture and rangeland conditions continued to decline, and livestock body condition scores declined as well. Water in the ponds was drying up quickly and has become an issue for some producers. Beef cattle producers were thinning their herds and some supplemental feeding began. Sale barns reported average volumes of cattle with higher percentages of cull cows and bulls. The number of early weaned calves began to increase as producers reduced stress on cows. Prices remained steady to slightly higher on all classes of beef cattle. Ranchers were feeding wildlife. Young coveys of bobwhite quail were starting to appear in many areas. Feed prices remained high at local feed stores, and the demand for hay increased with prices ranging from $70-$80 per round bale.