Optimizing genetics to advance controlled environment agriculture

Texas A&M AgriLife Research plant breeder brings new dimension to indoor farming innovation

Texas A&M AgriLife is adding crucial expertise to help guide future innovations in controlled environment horticulture as the burgeoning field continues to evolve.

Krishna Bhattarai, Ph.D., Texas A&M AgriLife Research plant breeder for controlled environment horticulture and assistant professor, has joined the Texas A&M College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Department of Horticultural Sciences. His research uses genetics and genomics to develop new horticulture crop cultivars specifically for controlled environment production.

Bhattarai’s research will be performed at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center in Dallas.

Strategic hire for controlled environment horticulture

Amit Dhingra, Ph.D., head of the Department of Horticultural Sciences, said Bhattarai’s hiring is a major step forward for the controlled environment horticulture program. He said technological advances have spurred much of the burgeoning field’s momentum, and Bhattarai’s arrival and focus on optimization of plant genetics in these systems comes at a critical time.

Dhingra said he believes the next step in the evolution of controlled environment horticulture is cohesion between plant genetics and the grow systems they support. The idea is not only to optimize yields but also focus on other cultivar characteristics like nutritional density and growth habit as well as aesthetics and flavor.

Daniel Leskovar, Ph.D., director at the Dallas center, said Bhattarai’s hire resulted from the strategic plan and vision of the controlled environment horticulture program at Texas A&M AgriLife.

“His expertise in plant breeding and phenotyping tools will provide very valuable synergy to our growing CEH multidisciplinary programs at Texas A&M University,” he said.

“Specifically, his expertise in plant breeding and genetics focused on developing new fruits and vegetable cultivars with improved resource use of efficient traits, disease and abiotic stress resistance, and with high nutritional and sensorial quality will ultimately benefit consumers, as well as the controlled environment growers and industry.”

About the controlled environment program

The controlled environment program at the Dallas center includes small-acreage/urban horticulturists, Joe Masabni, Ph.D., and Genhua Niu, Ph.D., both professors in the Department of Horticultural Sciences; Azlan Zahid, agriculture engineer from the Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering and entomologist, Arash Kheirodin, Ph.D., in the Department of Entomology. The team also includes Shuyang Zhen, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Horticultural Sciences, College Station.

Dhingra said Bhattarai’s arrival provides important expertise for the program’s holistic approach, making Texas A&M an innovator and leader in the field.

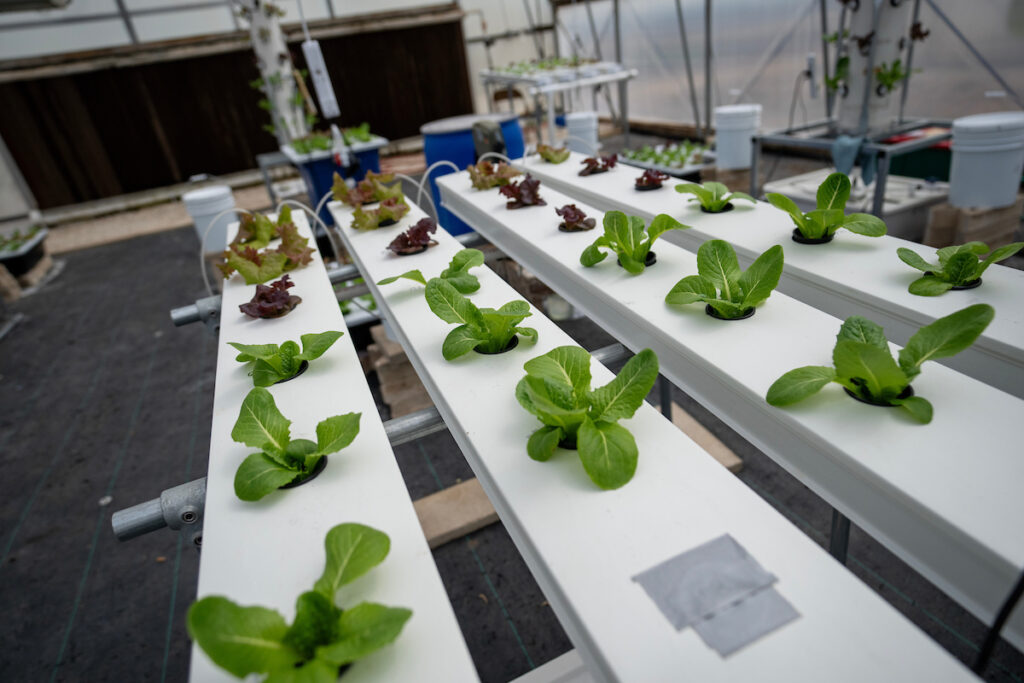

Researchers in the controlled environment horticulture program are experimenting with plants in a range of technologies that include long-standing methods like high tunnels and greenhouses and aquaponic and hydroponic systems.

They are also engaged in concepts like precision agriculture that rely on innovative technologies such as remote sensors to collect a range of data related to environmental and plant conditions. Sensing technology allows growers to incorporate other cutting-edge advancements like automation, robotics and artificial intelligence to manage plants.

“The next frontier in controlled environment production of horticultural crops is plant genetics,” Dhingra said. “We hope to increase the efficiency, sustainability and profitability for controlled environment growers by harnessing the genetic potential in plant material so that crops perform at optimal levels in these systems.”

Research in cultivar development to spur innovation

Bhattarai said he is aware of only one other plant breeder conducting public research dedicated to controlled environment production.

“A lot of research has been done on the structural and software programming side of controlled environment horticulture, but plant breeding specifically for those systems is lagging,” he said. “Cultivar development dedicated to controlled environment production is a field where there is a lot of opportunity to explore and contribute.”

Bhattarai’s previous research covered a broad range of horticultural crops, including flowers, fruits and vegetables.

Bacterial leaf spot resistance was the focal point of his research as a graduate research assistant in the North Carolina State University tomato breeding program. The disease is problematic for open-field tomato production.

In 2014, while a master’s student at the University of Florida, his focus shifted to ornamental plants, including the prevention of powdery mildew in cut flowers like Gerbera daisies.

Bhattarai’s research took another turn as a postdoctorate researcher at the University of California, Davis. Instead of breeding for plant disease resistance, he started analyzing genomic regions of strawberries in search of improved aroma and flavor.

“Since I have experience in all three of these important commodities, I thought I could deliver some good research that could impact plant breeding for controlled environment production in Texas,” he said. “We have seen tremendous growth of controlled environment production in Texas, and that makes Texas A&M an ideal place to be.”

Creating horticultural crop options

Controlled environment horticulture is emerging as a sustainable production method that can supplement traditional field production. As agriculture grapples with the potential impacts of climate change, water scarcity, land fragmentation and other challenges, systems that optimize resources, operate within small footprints and are not subject to the whims of Mother Nature continue to gain momentum.

Bhattarai said Texas is rapidly becoming a leader in controlled environment production, which puts Texas A&M AgriLife in a position to help the industry and producers navigate challenges. Breeding plants to optimize their uptake of water and fertilizer is a focus, but he is also looking at genes that determine plant structure and inflorescence to maximize yields in limited space.

According to grower surveys, he said many of these systems are dedicated to leafy green production, but Bhattarai wants to expand grower options and crop variety.

“Producers have to be profitable, and the ability to harness traits in cultivars for these targeted environments will be a critical part of the industry’s evolution,” he said. “The genetic side of innovation in this field will optimize technological innovations in these systems.”

Optimizing crop value for growers

Using genetic tools to identify and harness traits for specific growing systems will drive system optimization and industry sustainability, Bhattarai said.

For instance, in hydroponic systems, plants do not need high root biomass because nutrients are readily available. Bhattarai will select for cultivars producing higher volumes of the consumable products, whether fruit, shoots or leaves, for hydroponic growers. Genetics influencing inflorescence could also be chosen to optimize the system’s ability to automate the crop harvest.

Identifying and expressing plant genes that open pathways to better flavors, better nutrition and other distinct characteristics will help controlled environment producers grow premium produce, Bhattarai said. Plant breeding programs will also help create high-value fruit and vegetables that are distinct in the marketplace.

“The idea is to give controlled environment growers options and to optimize those options,” Bhattarai said.