USDA announces new plant biotechnology regulations

Texas A&M readies for greater research advances through gene editing

New plant biotechnology regulations announced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, APHIS, are a breakthrough for utilizing genetic engineering and gene editing to improve plants for a more resilient and safe agriculture system, according to a Texas A&M University leader.

David Baltensperger, Ph.D., head of Texas A&M’s Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, said the new regulations give scientists a significant advantage in commercializing genetic sequencing advances at a lower cost.

The new Sustainable, Ecological, Consistent, Uniform, Responsible, Efficient, or SECURE, biotechnology regulations have been announced. APHIS will host two technical webinars June 24 and Aug. 5 to review the confirmation-of-exemption process and give stakeholders the opportunity to ask questions. Registration for the webinars is available on the APHIS website [registration closed].

Beginning on Aug. 17, developers will be able to start submitting confirmation requests. To help stakeholders prepare prior to the implementation date, APHIS has updated its Confidential Business Information guidance and posted frequently asked questions to the APHIS SECURE webpage [registration closed].

Biotechnology regulation changes

Under the SECURE rule, plants may be designated as exempt from regulation if they fall under one of three categories:

- Plants with certain modifications that could otherwise have been achieved through conventional breeding.

- Plants with crop/trait combinations that were previously reviewed and are unlikely to pose an increased plant pest risk.

- Specific plants determined to not be regulated by APHIS pursuant to its “Am I Regulated?” process.

Baltensperger said APHIS officials visited Texas A&M and allowed the scientists there to bring up their concerns about safety.

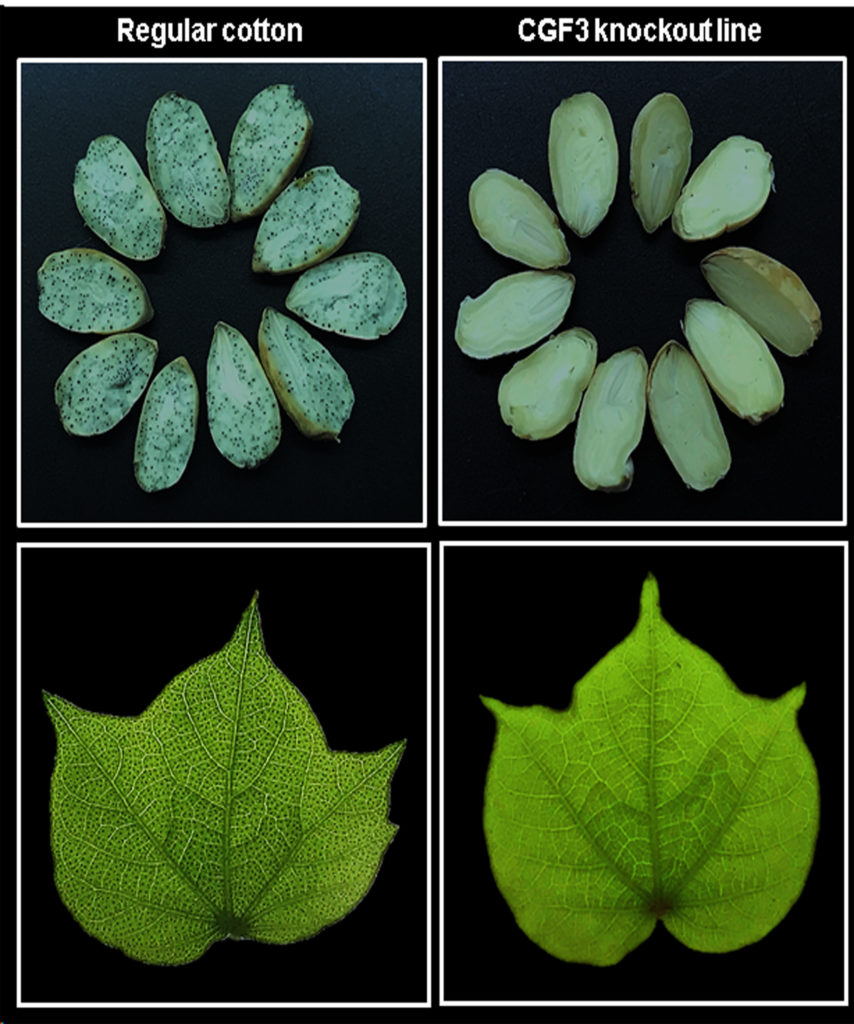

Keerti Rathore, Ph.D., a Texas A&M AgriLife Research plant biotechnologist in the Texas A&M Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, College Station, and researcher of plant genomics and biotechnology, and his team developed, tested and obtained deregulation for the transgenic cotton plant – TAM66274. Rathore was contacted during the writing of the regulations and his work was utilized as an example.

Moving forward at Texas A&M AgriLife

“These guidelines will help scientists like Dr. Rathore get approval through regulatory guidelines on GMOs much smoother, especially in determining what is and what isn’t a GMO regarding gene editing,” Baltensperger said.

“The biggest benefit about it is it will – with all our scientists – provide a much bigger opportunity to commercialize things like Dr. Rathore’s cotton,” he said.

“These regulatory reforms have been long overdue, especially after 25-plus years of cultivation and safe consumption of GMOs in the U.S. and several other countries,” Rathore said. “It is my hope that these reforms in the U.S. will serve as an example and encourage the regulators in other countries to ease their regulatory burden that countries where hunger and malnutrition are prevalent can also benefit from the advances in genetic engineering.”

Texas A&M has made huge advances in the last few years in gene editing and molecular technology. Key to that process has been Michael Thomson, Ph.D., and his high throughput gene-editing lab, as well as the transformation facility that goes with it in the Institute for Plant Genomics and Biotechnology, Baltensperger said.

“I think the new SECURE biotechnology regulations will help accelerate our transition from using gene editing primarily for research into a tool that plant breeders can begin to use for novel trait development for improved nutrition and stress tolerance,” Thomson said. “It also helps lower the bar for the amount of investment required for commercialization of gene-edited crops, allowing these new technologies to impact up-and-coming crops, in addition to mainstays such as cotton, wheat, sorghum and rice.”

Baltensperger said the next step and what “really gives us a step up is the gene sequencing abilities” through AgriLife’s Genomics and Bioinformatics Service, led by Charles Johnson, Ph.D., executive director, College Station.

“As an international leader in agrigenomics technology development and application, we have the capacity to process and sequence thousands of samples per week for screening,” Johnson said. “We expect the new regulations will greatly expand the use of the latest in crop improvement methods, and we are preparing to be able to address the significant growth in the use of sequencing technology.”

Baltensperger said Johnson “tells us if we got the editing done right and helps us ensure we are just selecting the gene we need and not bringing any others with it. You want to make sure you don’t add something in that can have deleterious effects.”

Simply put, he said this whole process allows researchers to select a beneficial gene that exists in a poor genetic background and be able to cut it out and put it into a variety that has been well-adapted to this area.

“We can insert it and not have to go through years of cross breeding.”