Texas A&M Forest Service employees, retirees recall Columbia recovery mission

20th anniversary on Feb. 1

Bill Oates was renovating his Nacogdoches home when he thought the rumbling he heard was coming from his daughter running around the house.

John Gill was working a weekend job on a logging crew in East Texas when his boss asked if he had seen anything falling from the sky.

Jake Donellan believed the boom he heard was a vehicle crash at an intersection near his Marshall home.

Marilynn Grossman was driving through College Station when she saw a streak cross the horizon, “like a shooting star, but out of place for that time of day.”

What they had all heard was the space shuttle Columbia disintegrating over Texas as it re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere on Feb. 1, 2003.

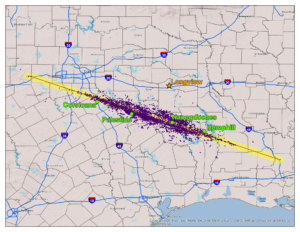

There were no survivors among the seven astronauts on the NASA STS-107 shuttle, which was returning from a 16-day mission. The shuttle’s explosion sparked a massive ground search in an effort to recover the astronauts’ remains and shuttle debris that was scattered across heavily forested areas over multiple counties. Texas A&M Forest Service served as a lead state agency in the recovery mission, managing exhaustive ground searches throughout the East Texas debris field.

Memorial dedication

On Feb. 1, the 20th anniversary of the Columbia disaster, Texas A&M Forest Service, along with NASA, the U.S. Forest Service and the city of Nacogdoches, will rededicate the seven trees planted in 2003 in memory of the shuttle crew members.

The event in Banita Creek Park will include the unveiling of an informational marker and the dedication of two newly planted trees. The new trees will honor Charles Krenek and Jules “Buzz” Mier Jr., who died in a helicopter crash during the search for shuttle debris.

Mier, a U.S. Army veteran, was a pilot under contract with the U.S. Forest Service. Krenek, a Texas A&M Forest Service aviation specialist, was serving as a search manager. Krenek was well-liked and during his over 26-year career with the agency had earned a reputation for his commitment to serving others.

“He was truly a good man,” said Oates, who worked with Krenek and is now Texas A&M Forest Service associate director. “His death hit me as hard as any other death that I’ve experienced because of the type of person he was. I think about him frequently.”

Like a family

Texas A&M Forest Service employees and retired staff members who played a role in the 2003 search for Columbia and her crew describe the experience as meaningful. Many noted the spirit of cooperation, the bonds with other responders and the important role their training played in preparing them for the challenges of the task.

Oates, who worked in a planning role from a command post in Lufkin during the search for Columbia’s debris, said watching the community come together alongside multiple federal, state and local agencies was inspiring.

“I’ve never been involved with anything like that before,” he said. “People worked really hard to help the nation and figure out how to start the healing process. It was very gratifying to be involved in something like that.”

James Hull, who served as agency director from 1996 to 2008, said the relationships among responders and NASA officials seemed natural.

“I’ve always looked at the Forest Service as a well-organized family. We respect each other and work well together,” Hull said. “And we discovered the same thing with NASA. They have that same close-knit bond between their employees, and as it developed, it felt more like family helping family than a working relationship.”

Tom Boggus, who retired as Texas A&M Forest Service director in 2021 and was serving as associate director and deputy state forester in 2003, also recalled the feeling of being connected to a larger family.

“One thing that struck me was the community of the astronauts, how close they are and the relationships that they have,” Boggus said. “It was a really strong, close-knit group of folks, and we got to be part of that. We got adopted into the NASA family.”

While some personality clashes might be expected amid the stress and chaos of such an emergency, Oates said, the overall experience was one of solidarity and cooperation.

“Firefighters, astronauts and engineers all have egos, but that all got put aside,” he said. “It just goes to the spirit of the American people and their ability to come together when needed.”

Unsung heroes

During the initial stages of the response, representatives from dozens of state and federal agencies converged on the rural East Texas communities, but direction was lacking, Hull said.

“We didn’t go in there trying to claim leadership, but over a few days, federal agencies started realizing that there was but one group in all these massive amounts of people that seemed to have leadership, the ability to organize people and the personnel who could do it,” Hull said. “We also had a familiarity with the geography of the area and relationships with the local people and community leaders. We just sort of gravitated by mutual consent of everybody that we had what it took to lead something like this.”

At the time, the incident command system had not been standardized nationally, but through its management of wildfires and other emergency response situations, Texas A&M Forest Service knew the value of having a structured organization and chain of command, defined communication channels and a planning process.

“It’s a way of bringing together agencies and organizations to fulfill a single mission,” said Mark Stanford, who was the agency’s chief of fire operations in 2003. “What we did, which started on the second day, was produce an incident action plan. Then our role morphed into implementing the incident command system because the leadership there started to recognize what we could provide to help them accomplish their mission.”

Stanford said the idea to utilize wildland firefighting crews in the search came after the Texas Department of Public Safety and the Texas Army National Guard were reassigned because of an increase in the national threat level coinciding with the start of the war in Iraq.

Stanford, who retired in 2022 as associate director for forest resource protection and fire chief, would not take any personal credit for leading the agency’s response.

“I was just part of the team,” he said.

Instead, Stanford commended people working behind the scenes, doing whatever they could to help. He called them unsung heroes.

“Everyone involved had a passion for getting the job done,” he said. “It makes you feel really positive about Americans and Texans. If something happens, they’re going to be there to assist their neighbors, the state and country.”

Hull said everyone he talked to said the agency “far exceeded” expectations in its role to find and retrieve shuttle debris.

“We got the job done,” Boggus said. “It’s something that this agency should be proud of. It’s one of our milestones, one of those times in this agency’s history that you’re going to look back on and go, ‘Wow, that was something to be remembered.’”

In all, the ground search and recovery lasted 100 days, covered 680,750 acres, and involved more than 25,000 people.

‘It was an honor’

Jake Donellan, Texas A&M Forest Service East Texas Operations Department head, was a staff forester in 2003. He called his boss asking to be involved in the recovery effort as soon as he learned the shuttle had been lost.

“A staff forester normally wouldn’t have a role in emergency response,” he said. “But the nation had just experienced 9/11, and I wanted to help.”

Donellan was assigned to search for debris from an operational base in Cherokee County, where he met Krenek.

“It was my first interaction with Charles,” he said. “I’d heard he was a character, and that proved to be true.”

Donellan said the loss of the space shuttle unified the country, with federal, state and local officials working alongside an army of volunteers searching rough terrain in uncomfortable weather.

“I think our agency and the people involved can take great pride in how much was accomplished,” he said. “It’s a testament to all the people who were walking shoulder-to-shoulder in some of the nastiest conditions.”

In all, the ground search and recovery lasted 100 days, covered 680,750 acres, and involved more than 25,000 people. More than 82,000 pieces of material were recovered — about 38% of the shuttle — allowing NASA teams to pinpoint the cause of the shuttle failure to a debris strike on the left wing during launch.

“It was our job,” Donellan said, “but it was also about bringing those heroes home and what that meant to those families. It was an honor.”

Facing the challenge

By the beginning of March, 256 agency employees — about 70% of the staff at the time — had been mobilized as part of the effort.

Hull called himself the head cheerleader for the agency and said he never had any doubts about the qualifications of his team.

“They had the training and experience, and I did what I could to make sure everybody knew they had whatever resources they needed,” Hull said. “We wanted everybody to know that their job was important.”

Hull’s biggest concern was the amount of time employees were away from home and their normal duties.

“But they seemed to thrive on what they were doing,” he said. “There was never, ever a thought that I ever detected of being overwhelmed or that we might fail.”

Unforgettable

John Gill, Texas A&M Forest Service resource specialist, said the shuttle’s hypersonic re-entry shook his Newton County home, with pictures falling off the walls. Gill was assigned to a team in Hemphill responsible for cataloging parts that were recovered.

“We had a team of NASA engineers there who tried to identify every piece brought in,” Gill said. “It amazed me how much they knew about every part of the shuttle. They could identify even charred pieces no bigger than your hand.”

Gill said he was grateful to have a role in the recovery mission.

“I’ve been on many assignments in my career, but the Columbia disaster is one I’ll never forget,” he said.

Then-district forester Chris Brown worked at a Nacogdoches site tagging and recording shuttle debris brought in by search teams. One of the community volunteers at the site was a retired NASA contractor.

“He had worked on the International Space Station,” Brown said, “and he could tell us what all the parts were. He said it was therapy for him to be able to help in some way.”

Brown, now a Texas A&M Forest Service program leader, later was assigned to a GIS team producing maps for the searchers.

“We would make the map and classify the vegetation types to determine the time needed to search each grid,” he said. “We made them so the incident management teams could figure out how many people they would need to search a particular area and how long it would take.”

Brown said he was proud of the agency’s accomplishments in the search.

“It was a huge effort with everyone coming together,” he said. “It was neat to see the way the astronauts connected. They were a family, just like we are, and that’s something special.”

Rich Gray said the 100-day effort to recover the shuttle from the East Texas debris field was awe-inspiring.

“Just the sheer number of different organizations that were mobilized, and everyone working together,” said Gray, who organized some of the initial searches before taking a role as a safety officer. “I think back on it with a lot of pride. It set the stage for establishing that this agency has the ability to function at that level, and more importantly, to be respected and trusted at that level.”

Gray, Texas A&M Forest Service chief regional fire coordinator, said the shuttle response also set the stage for a shift in technology.

“Some of the things that we take for granted today were the early technology that was being used then,” Gray said. “They mapped the debris field, down to the vegetation. It’s easily done now, but at the time, it was iconic. They looked at ways technology could help in the search and put it into practice.”

Boots on the ground

Marilynn Grossman had been hired in early 2003 as communications director, a new position for the agency. She was set to start on Feb. 3 but got called in early.

Grossman, who didn’t have a list of media contacts when she started, was responsible for disseminating information for the agency. She said she got a quick lesson in the fundamentals of the incident command system being used to manage the search and was impressed by the dedication of the search teams.

“I saw the talent within the agency,” she said. “A lot of people doubted that ‘those foresters’ were up to the task, but jumping right into this shuttle response taught me that we knew what we were doing. We were a lot more than trees.”

Grossman, who left the agency in 2008, said she’s never forgotten the dedication of the wildland firefighters involved in the search and their accomplishments of working through the tough conditions.

“I remember going to a firefighter camp and seeing a tent that had hundreds of pairs of boots they were trying to dry out,” she said. “They had to buy two or three pairs of boots per person just so they’d have dry boots every day.”

Always prepared

Retiree Boo Walker, who returns to duty for Texas A&M Forest Service each fire season, was on an out-of-state training assignment in early February and didn’t participate in the Columbia search until later in the month.

On his first morning of being involved with the search effort as the head of the agency’s aviation operations, he was sent into a meeting at the Lufkin command post.

“There were a bunch of astronauts and a bunch of federal government people in coats and ties, and they asked me what my plan was,” he said.

His said his training, instincts and experience on incident management teams kicked in, and he began outlining a detailed plan to divide the region into sections, deploy air attack platforms and establish safety protocols.

“They were glad that we were there and wanted to hear what we had to say,” Walker said. “NASA had their best people out here to help us, and we sent our best people to help them.”

Life-affirming mission

After the funeral for Mier and Krenek, Walker said everyone returned their focus on the work at hand.

“We had a mission, and we needed to complete it,” he said. “That’s what Charles would have wanted us to do.”

Hull said Krenek was a top employee in every way.

“Charles was one of those who led by example,” said Hull, noting Krenek’s experience could have qualified him for a job in the command post. “But he led by doing, which is why he was in that helicopter.”

Several people involved in the agency’s response said their experience in the ground search, combined with the helicopter crash that killed a colleague, gave them a greater appreciation for life.

“Those astronauts probably never thought that they wouldn’t make it back home to see their families,” Gill said. “Live every day like it could be your last.”

Oates agreed: “It makes you realize what’s really important.”