AgriLife Research expert uses math to predict environmental impacts of livestock production

‘Smart-farming’ approach models sustainable, intensive protein production

In an effort to make sure our animal protein supply is sustainable, a Texas A&M AgriLife researcher is using mathematical modeling to connect the dots between increasing production efficiency in livestock operations and minimizing environmental impacts.

Luis Tedeschi, Ph.D., an AgriLife Research ruminant nutritionist, and his team in the Texas A&M University Department of Animal Science recently published a paper on sustainable livestock intensification, Modelling a Sustainable Future for Livestock Production, in Scientia.

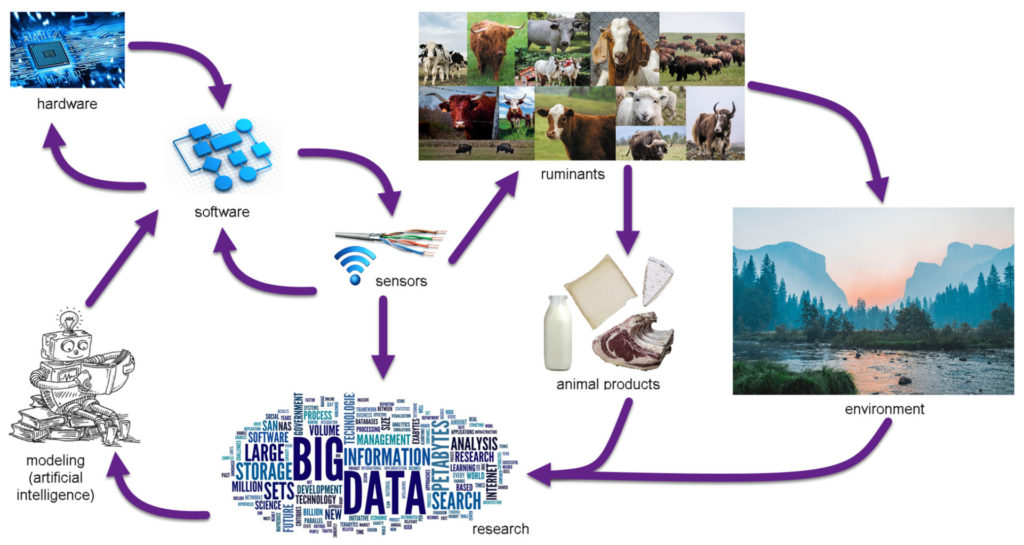

The team concluded that an integrated smart-farming approach employing innovative pasture systems and modeling-based decision support tools could help create more sustainable livestock systems.

In the Scientia paper, Tedeschi said it is clear that sustainable intensification does not result solely from improved biological and physical processes. Such improvements also require managing the system appropriately and intelligently in an integrated, holistic way. Thus, modeling-based, integrated decision-support systems could form the backbone of future sustainable intensification of the livestock industry.

Environmental impact of livestock production

With most current food production systems focusing on maximum productivity and profitability, there is concern that protecting or regenerating the environment is not part of the equation.

“With a world population that is predicted to reach 9.55 billion by 2050, increasing pressure is being placed on global food production,” the team wrote. “Doing so while reducing the impact on the environment requires crop, soil and animal scientists around the world to come up with quick and effective solutions.”

Tedeschi said livestock production is often criticized as a critical global contributor to greenhouse gases, with some estimating it accounts for up to 14% of emissions. While there is room for improvement, that number, in reality, is less than about 6% in the U.S. However, those emission levels vary among countries, depending on the emissions of other sectors, mainly the energy sector.

“When it comes to the environment, everyone talks about sustainability, but nobody knows for sure how to make that happen,” Tedeschi said. “Some people might say stop eating beef while others say stop driving your car. It’s a guessing game. Science can help us to find the way.”

Sustainability doesn’t have to be a guessing game when it comes to livestock nutrition and environmental impacts, he said.

“We have the scientific knowledge of ruminant nutrition to accurately understand how what we feed impacts the environment. We’ve developed the mathematical models, and while they may not be 100% accurate, they definitively can tell us if our changes are going to be positive or negative, on the bottom line, to the environment.”

Modeling feeding impacts on the environment

Tedeschi said modeling requires looking at the past, present and future, as well as taking into account high-tech developments such as remote sensing and ground-based instrumentation, communications, weather forecasting technologies, sensor technologies, decision-support systems and other management tools.

“They have the ability to enable users to quickly evaluate multiple scenarios of production and choose options that are more acceptable, sustainable and resilient,” he said.

These tools help livestock producers manage their risks, adapt to changing environments, make management decisions and even improve efficiency by automating some tasks, such as feeding schedules and early disease detection.

The whole idea, Tedeschi said, is to combine all the concepts of livestock production, nutrition and sustainability into computer models.

“We need actual facts about cattle production and how it affects the environment in terms of greenhouse production and sustainability,” he said. “We see a lot of estimates, but they are not realistic. We’ve been working on these computer mathematical models to predict the real effect of the animal production on our environment. We are learning how to feed them to lessen or decrease their impact on the environment.”

Sustainable livestock intensification requires utilizing science to analyze ecosystems where the livestock are and determine what management practices would minimize environmental impact.

“We want to empower our livestock producers and stakeholders to ‘know before it happens’,” Tedeschi said. “We have developed a system where they can mathematically model management changes to determine what differences they will make before implementing the actual changes.”

Tedeschi said his research group has created a suite of models aimed at livestock intensification through the betterment of animal nutrition. Each model has a specific objective, but the key calculation logic can be used together in different applications and applied to diverse livestock operations, including beef, dairy, sheep and goats.

These models let the producer identify areas in the diet where changes can be made to improve performance, he said. The nutrition models are already in use across the globe. In particular, the cattle growth model is used by the feedlot industry in Texas as well as by livestock operations throughout the world. The software has mostly been downloaded and registered in the U.S., Mexico, Canada, Colombia, Brazil, Argentina, United Kingdom, Italy, Turkey, Iran, China and Australia.

Smart farm modeling

“If I replace or change the amount of a specific feed, how much methane will my animals produce at the end of the day?” Such questions, along with the cost of production and environmental inputs, can be answered simply with modeling, Tedeschi said.

Mathematical modeling — in association with sensors that have become available in the last five to 10 years — allows scientists to measure everything.

“We can collect information on a minute-by-minute basis if we want,” Tedeschi said. “Is the animal getting physical activity, when and how fast is the animal eating, how far did they walk or move to get water — we can use all of this information to follow the growth and development of the animal. We can then build in information about the climate and link all of that together. When we take all of this information, we can build an artificial intelligence model that can identify which animal performs better in different situations.”

Tedeschi said in his lab, his team is able to use in vitro gas production to test the quality of the feed or pasture and determine how and when to supplement the livestock based on that information.

“It makes intervention more accurate,” he said, “making us more aware of what should be fed instead of just routinely feeding supplements.”

“We can improve and increase production as producers, but at the same time be sustainable and mindful of the environments,” Tedeschi said. “We have to use everything that we know, combine and coordinate it, to make better decisions that allow environmental, economic and social sustainability.”

The team concluded that future iterations and development of these tools must account for the effects of climate change on animal welfare, nutrient needs and productivity. The tools must also accomodate increased consumer demand for high-quality, protein-rich food, while at the same time minimizing livestock’s environmental carbon and water footprint.