Pasture-cropping practice could improve degraded Texas grassland soils

Texas A&M AgriLife-led research to analyze method’s effectiveness, economics

Adopting the ecologically sensitive, low-cost conservation management pasture-cropping practice could help landowners regain the health and resiliency of soils sustaining degradation over the years.

Pasture cropping, a relatively new and innovative land management system, integrates direct seeding of cool-season annual crops into dormant perennial warm-season grasses. It was pioneered by Colin Seis, an Australian farmer.

Now the potential for implementation of the practice in the Southern Great Plains is being investigated by a Texas A&M AgriLife-led team of researchers through the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture, NIFA, grant-funded project “Enhancing Soil Ecosystem Health and Resilience Through Pasture Cropping.”

The team consists of Srinivasulu Ale, Ph.D., project lead and Texas A&M University Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering geospatial hydrologist; Richard Teague, Ph.D., Department of Rangeland, Wildlife and Fisheries Management range ecologist; and Paul DeLaune, Ph.D., Department of Soil and Crop Sciences environmental soil scientist, all College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and Texas A&M AgriLife Research faculty at Vernon.

They are joined by Tim Steffens, Ph.D., Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service range specialist at West Texas A&M University at Canyon, and Tong Wang, Ph.D., advanced production specialist at South Dakota State University. The team is also consulting with Seis as they build and conduct their research.

Ale said while some ranchers have already adopted the practice on smaller scales, many are looking for guidance – information on the best crops, the best time to plant and terminate/harvest them, and how benefits vary between wet, normal and dry years.

“We expect to be able to answer these questions at the end of our four-year project based on all the data we collect and modeling we conduct,” he said.

Getting to the root of the matter

Continuous and heavy grazing pressure since the introduction of conventional livestock grazing has resulted in degraded grassland soils, largely due to a combination of a lack of species diversity and diminished soil inputs of organic material from plant roots, Steffens said.

The pasture-cropping practice has helped rebuild soil organic matter and improve soil structure, infiltration and water holding capacity in Australia, he said.

“The hypothesis is that adding growing roots, root exudates and mycorrhizal fungi in the colder parts of the year provides an additional amount of organic material when the warm-season grasses are not growing, but when decomposition is still occurring,” Steffens said. “This boost of organic material and the enhanced microbial activity it triggers are what drives better ecological function of the soil.”

The project aims to evaluate these soil health benefits through a combination of field experiments, unmanned aerial vehicle or UAV-based measurements, environmental modeling and economic analyses.

Through these measurements and simulations, the team will assess the ranch- and watershed-scale improvements in ecosystem services from pasture cropping and analyze the economics compared to conventional practices under different weather and market conditions.

Securing soil resources

Soil degradation can result in elevated soil erosion, soil organic carbon loss, nutrient imbalance, soil sealing, acidification, salinization, contamination, waterlogging, compaction and loss of soil biodiversity.

DeLaune said introducing growing plants during the winter months will not only increase microbial activity, but also provide increased soil cover and protection, supplemental forage for grazing and subsequent cycling of soil nutrients.

“Our goal is to evaluate the overall effect of pasture cropping on soil health and function,” he said. “In our cropping systems, we have observed trends in improved microbial activity with an extended period of living roots over the year. Additionally, we have observed improved physical properties that increase water infiltration, reduce runoff and improve water quality.”

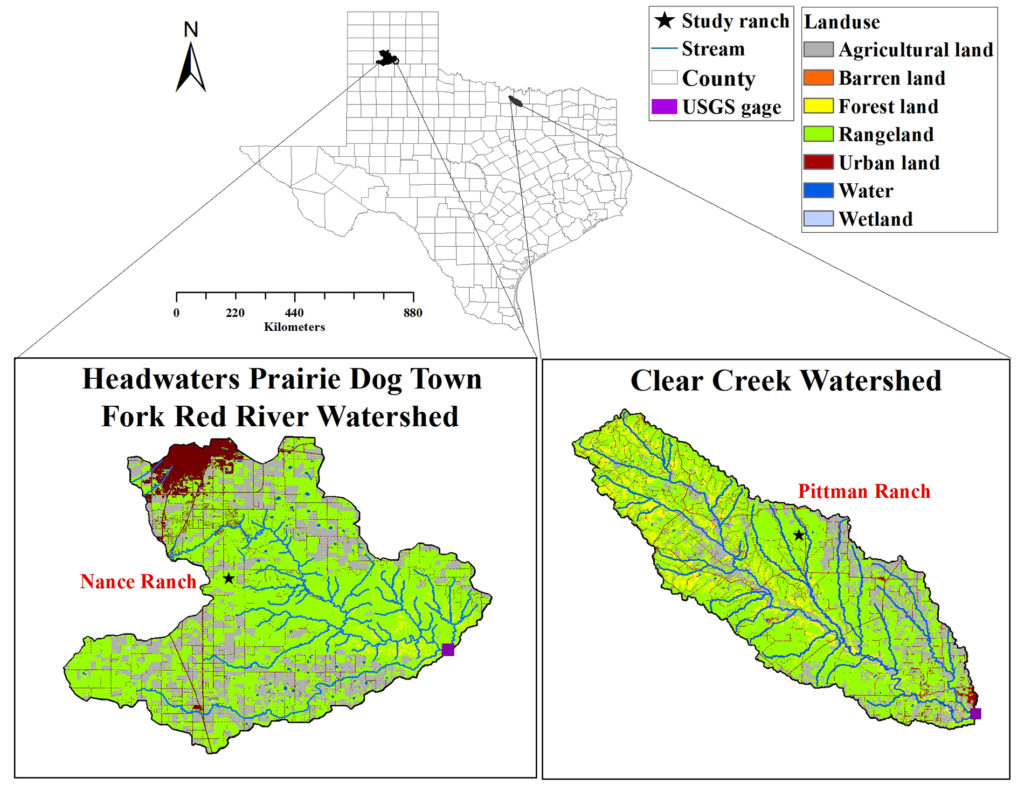

The pasture-cropping field experiments will be conducted at the West Texas A&M University’s Nance Ranch near Canyon and at the Dixon Water Foundation’s Pittman Ranch near Muenster. Modeling efforts will focus on the headwaters of the Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red River watershed in the Texas Panhandle, which includes the Nance Ranch; and the Clear Creek watershed in North Central Texas, which contains the Pittman Ranch.

The pasture will be grazed short one to two days prior to planting, and then very similar to no-till wheat, the seeds will be drilled directly into the grassland during the fall. The winter wheat will be an added source of green winter grazing that can decrease the cost of supplementary feeding in winter. And, in wetter years, it also might be possible to harvest a grain crop.

However, in most years, prior to the warm-season grasses starting to green in the spring, the wheat will be grazed off so the grass growth is not hampered.

Teague said the process will be conducted on one-quarter or less of the pasture each year, and that pasture will not be grazed again until the other summer pastures have all been appropriately grazed in rotation to allow maximum recovery.

“This practice requires excellent adaptive multi-paddock grazing of the native grassland to build soil health/carbon as the base,” he said. “Doing the pasture cropping more often than every four years would likely negate this or even lower soil carbon in time. Conducting the practice every year would degrade the solid base of the healthy summer growing permanent pasture soil health, even in wetter parts of the world.”

Beyond the field trials

Ale said while Steffens, Teague and DeLaune will conduct the field experiments and data collection, he will be evaluating ecosystem models with their data so he can then run long-term simulations.

With modeling, he said he can determine what happens if the practice is carried out for 10 or 20 years, build in projected future weather changes, and assess the potential of pasture cropping in mitigating the negative effects of climate variability and change on soil ecosystem services.

“They will be doing these experiments on a ranch scale, but I can model it on a watershed basis – measure the holistic benefits if all ranchers in a watershed do it,” Ale said.

After conducting the experiments over four years and analyzing the data to compare the various soil health indicators, Wang will provide an economic analysis of all the practices and improvements.

Steffens said once the project is complete, they plan to incorporate their findings into the various in-depth grazing and ranch management schools he conducts.