Ogallala Aquifer depletion: Situation to manage, not problem to solve

Courage, experimentation, voices needed to drive change

The Ogallala Aquifer’s future requires not just adapting to declining water levels, but the involvement of a wide range of participants comfortable with innovation who will help manage the situation and drive future changes.

That was the message heard by more than 200 participants from across eight states who listened in and identified key steps in working together during the recent two-day Virtual Ogallala Aquifer Summit. The event was led by the U.S. Department of Agriculture-funded Ogallala Water Coordinated Agriculture Project, CAP, which includes Texas A&M AgriLife. The group partners with the Kansas Water Office and USDA’s Agriculture Research Service-supported Ogallala Aquifer Program to coordinate this event with additional support from other individuals from all eight states overlying the Ogallala Aquifer.

“Technological innovation, financial and economic conditions, infrastructure changes, social values – all these factors drive change,” said John Tracy, Ph.D., director of the Texas Water Resources Institute, which is a partnering agency in the Ogallala Aquifer Program.

Often people feel the need to solve the issue of declining groundwater across many parts of the aquifer, when in fact, what is needed is to look at how we manage change, Tracy said. Adaptive management is about driving the change — realizing it is coming and trying to affect what is happening rather than just responding.

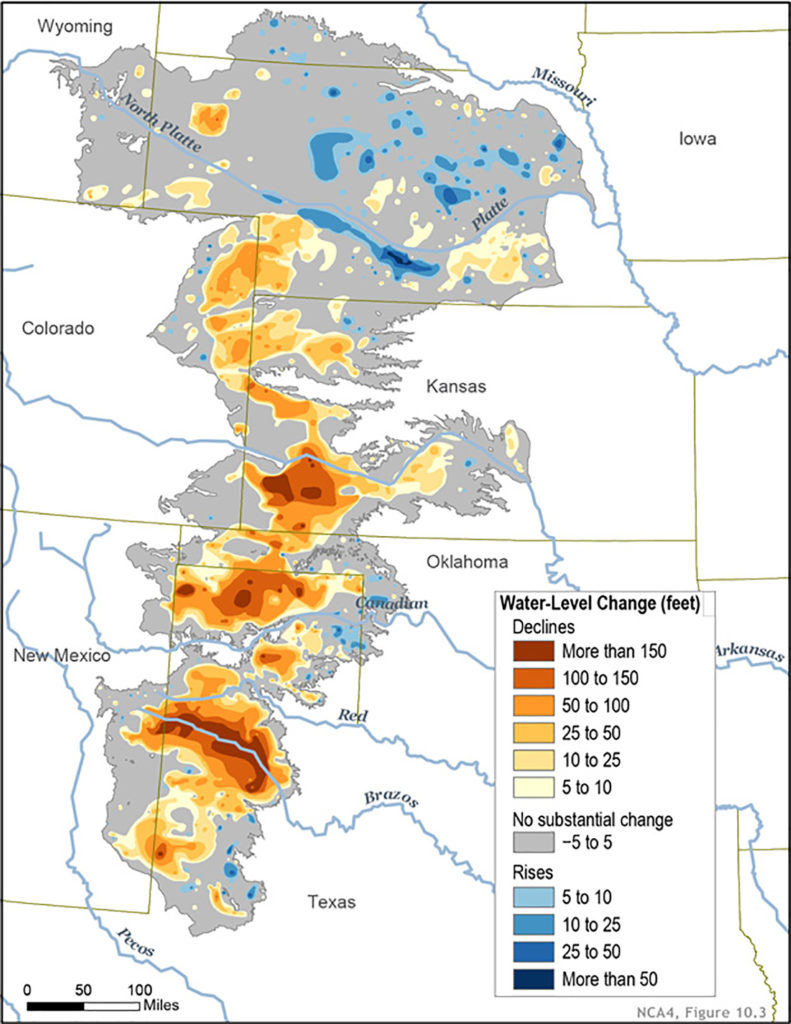

“So, large regions of the Ogallala are going to run out of water, particularly in the Southern High Plains – how are we going to embrace that and not just respond to the change?” he said. “Two important factors: first, this summit; have productive and transparent dialogue to move forward.

“The second thing we need to embrace is rethinking how we approach the changes happening in the Ogallala — this is not a problem to be solved; this is a situation to be managed. We must move into the mindset of changing programs in order to get out in front of the situation. One of the most important activities is looking forward to how we drive this conversation and turn talk into action through consensus building that is the product of shared dialogue amongst all of us.”

Meeting of the minds

An inaugural eight-state summit, led by the Ogallala Water CAP and Kansas Water Office in 2018 focused on what actions were happening or could happen in terms of field management, science and, to some extent, policy.

After the 2018 summit, participants across the eight states helped lead the integration and merging of technology, the expansion of the Master Irrigator program into more states, as well as the development of new policies and incentives to support more conservation and other collaborative efforts. These efforts are helping develop a broader understanding of actions needed to address the region’s critical water issues.

The 2021 summit was intentionally framed to engage a broader community of actors.

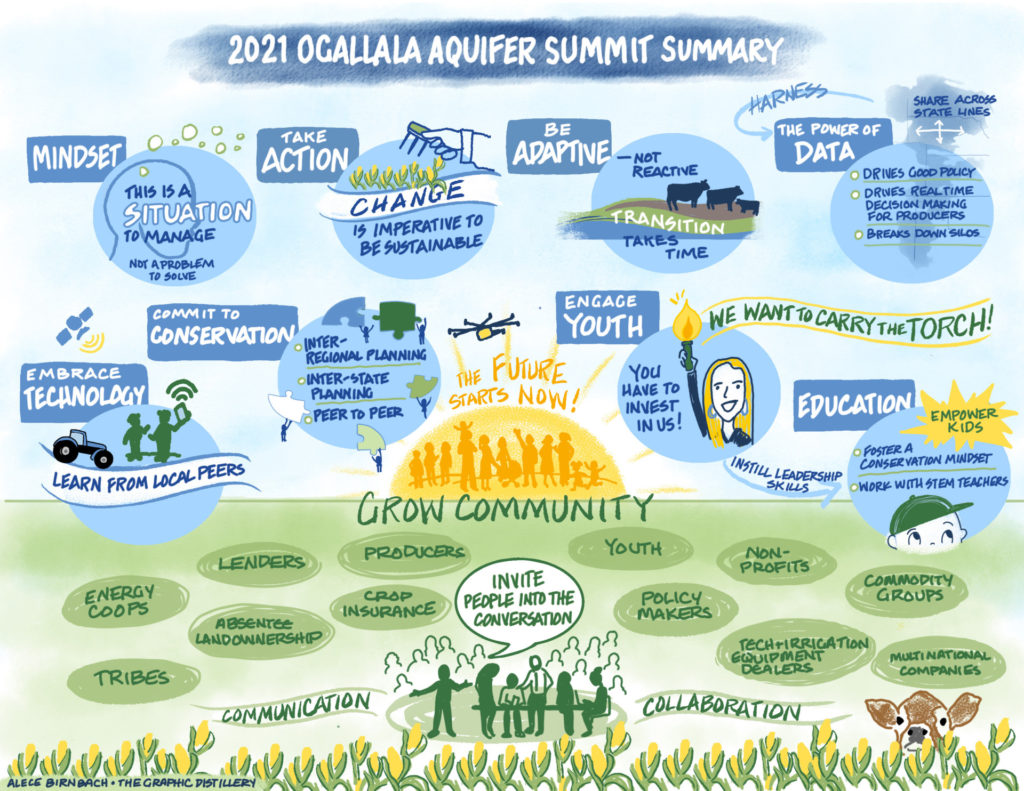

Joining the conversation were representatives of energy co-ops, lenders, producers, federal agencies in each state, youth, non-profits, policymakers, commodity groups, tech and irrigation equipment dealers and multinational companies. Participants identified other groups, including absentee landowners and tribal representatives, that should be invited and engaged as a focus area of the conversation at a future summit event.

Key messages that surfaced from the two days of conversations were:

– Change is imperative to be sustainable. You must be adaptive, not reactive. Transition takes time.

– Learn from each other using inter-regional, interstate and peer-to-peer planning.

– Be willing to experiment with new ideas.

– The power of data drives good policy and real-time decision making for producers and helps break down silos.

– Water is a basic critical infrastructure; we need enough water to support our rural economy, but all industries are dependent on water and it affects the overall economy.

– Producers carry the brunt of what we talk about financially, and keeping them profitable as long as possible must be a priority.

– Engage and invest in youth. Invite them to join and foster conversations that instill a conservation mindset not just among their peers but with a wide range of stakeholders.

Changing the mindset

The path forward begins with creating interest and providing education to the next generation of both producers and water conservation leaders. Fostering the transfer of knowledge between generations and developing leadership skills to position youth to step into groundwater district and other community leadership roles will be key.

David Smith, 4-H2O program coordinator with the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service, Bryan-College Station, described how the Texas 4-H Water Ambassadors program is creating water stewardship leaders.

The program provides an opportunity for youth to gain insight into water law, policy, planning and management, and potential career paths as they interact with representatives from state water agencies, educators, researchers, policymakers and water resource managers.

But education must also take place in the fields. It must provide an organized pathway where producers can find actions and dedicate the time needed to make a difference. Producer-to-producer learning approaches in partnership with university and industry, such as the Nebraska and Oklahoma Testing Ag Performance Solutions program, have been particularly effective.

Brent Auvermann, Ph.D., summit program chair and Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center director, Amarillo, said the adoption of technology can’t be taken for granted. Looking ahead, tech development and research must grapple with the human dimension of technology adoption.

“Technology will race ahead, but it will stay on the shelf until and unless we devise new ways to foster its adoption,” Auvermann said. “Using even a little bit more water than needed is a form of crop insurance and asking producers to rely on new technology to cut back on that water use increases the risk that they, their insurers and their lenders perceive.”

C.E. Williams, Panhandle Groundwater Conservation District general manager, White Deer, said when producers think about growing a crop, their concern shouldn’t be about bushels per acre — water is the limiting factor. They need to understand and invest in the technology that will ensure they are putting every drop in the right place.

“All the inputs you put in are important, but the bottom line is water,” Williams said. “Why did we use it? It is like money. You spend it; it is gone. What was your bottom line per water use? Rather than thinking of production in terms of bushels per acre, we should be thinking in terms of how many bushels per acre-inch or acre-foot of water used.”

Every drop saved adds up

We need to find a way to provide access to broad audience about the actions of many successful innovators who are having success with different precision management technologies and strategies, said Chuck West, Thornton Distinguished Chair in the Texas Tech University Department of Plant and Soil Science, Lubbock.

“There are a lot of little decisions that people can make all along the way that add up to considerable water savings,” West said.

Katie Ingels, director of communications with the Kansas Water Office, said several some of their Water Tech Farm producers are seeing the advantages of tech adoption, where a combination of slight adjustments in practice or integrating a new tool or strategy and related decisions each contribute some savings of money, time or water.

“There’s a mindset out there among some growers that they can’t make a tremendous difference because they are a smaller operation with only a few wells,” said panelist Cory Gilbert, founder of On Target Ag Solutions. “Every single system that adds to the acre-foot savings turns into a very big number very quickly in terms of conservation.”

Panelist Matt Long, producer and seed supplier, Leoti, Kansas, said water conservation is a quality of life issue.

“If you look at the communities you can see which ones are vibrant and they are the ones with a stable water supply that can support industry beyond cropping,” Long said. “Conserving water isn’t just about there being water for the future; it’s about having a community for the future. We have to have enough water to keep the people to keep the community.”

But at the same time, Auvermann said, communities need to be mindful of their water use.

“We city folks need to look no further than our front lawns to see why we’re in the pickle we’re in,” Auvermann said. “We run water down the curb to make sure our home’s appearance doesn’t suffer. Water is insurance for all of us.”

Building a path forward

Amy Kremen, Ogallala Water CAP project manager, Department of Soil and Crop Sciences at Colorado State University, said a continuing theme throughout the meeting was, “With limited water in the High Plains, the question is less about production that needs to feed the world’s population of 8 billion, it’s about keeping rural communities vital. We need to give people more flexible options that allow them to make decisions related to water use that are to their economic best advantage.”

Quality of life in these smaller communities, whether they are in Kansas or Texas or any of the states the Ogallala Aquifer supports, is what is important.

“We don’t want to dry up that life,” Kremen said. “We are all in this together. And together, we will come up with solutions better than any of us individually.”

Decisions must center on making conservation economical for agriculture producers, both short-term and with long-term sustainability, providing not only for the next generations on the farm, but for the sustainability of the local communities they support.

“We need to be willing to have uncomfortable conversations,” Auvermann said. “We need to talk candidly and be willing to entertain new, unfamiliar ideas. Sometimes we’ll make mistakes, but it’s not as though we’ve not been making them up to this point. Fear of making mistakes keeps us from innovating. Our dialogue has to be generous, congenial and optimistic to overcome that. We have to be trustworthy ourselves, and we have to be willing to trust.”

People are hungry to have these conversations, said Meagan Schipanski, Ph.D., associate professor, Department of Soil and Crop Sciences at Colorado State University and Ogallala Water CAP codirector.

“We need to have them happen in public, mini-summits or regional conversations,” Schipanski said. “We need to take on a stewardship that meets producer and community needs.”