Texas A&M AgriLife scientist publishes complete U.S.-Mexico borderlands aquifer map

Texas Water Resources Institute scientist Rosario Sanchez produces first-ever complete U.S.-Mexico transboundary aquifer map

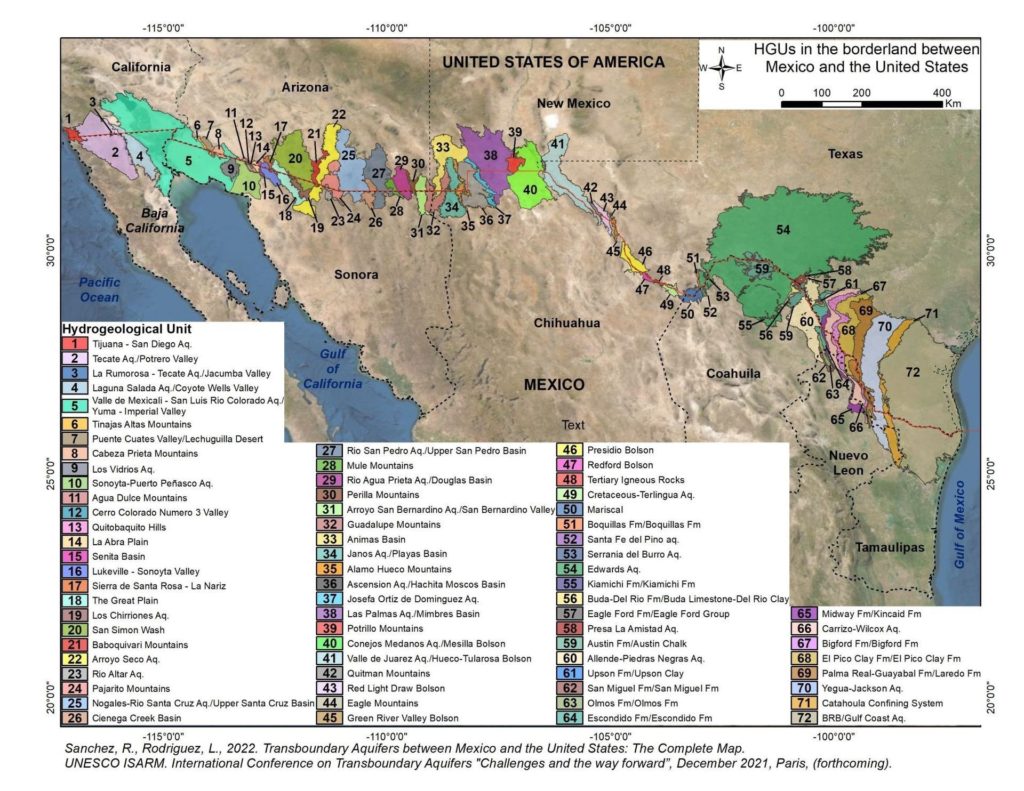

Worldwide, natural resource agencies and officials have counted the number of shared groundwater aquifers flowing beneath the U.S.-Mexico border at 11. But new research published by a Texas A&M AgriLife scientist reveals a more complicated picture: there are, in fact, 72 shared groundwater aquifers in the transboundary region.

Research and study realities

Rosario Sanchez, Ph.D., who has led this research for over a decade, recently published the first-ever complete map of the transboundary aquifers. As surface water supplies in the region are under increasing pressure from population growth, drought and climate change, Sanchez predicts these shared groundwater resources will receive more legal and governmental attention.

“We don’t have the luxury to keep ignoring the shared component of these resources,” she said. “We have to address this sooner or later, because the less we know, the more vulnerable we are.”

Sanchez is a senior research scientist for the Texas Water Resources Institute, TWRI, part of Texas A&M AgriLife. She is also director of the Permanent Forum of Binational Waters and leads the Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Act program for the state of Texas. Laura Rodriguez, Ph.D. candidate in Texas A&M’s Water Management and Hydrological Sciences graduate program, also contributed to and co-authored the research.

Combining years of geological and hydrological research, the map shows five shared aquifers between Baja California and California, 26 between Sonora and Arizona, and 33 between Texas and the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas. The researchers found 45% of the 72 aquifers to be in “good to moderate” condition.

“Overall, this study reflects two essential realities: half of the border region area has good aquifer conditions, and second, those shared aquifer systems are indiscriminately used by both countries without any legal framework regulating their extraction and management,” the study states.

Unknowns about border groundwater supplies

Shared groundwater resources between the U.S. and Mexico have been largely ignored at the binational level, and few funding opportunities for continued research exist, Sanchez said. As a result, there is much that researchers and policymakers do not know about groundwater supplies along the U.S.-Mexico border.

“We don’t know how much water has been withdrawn,” she said. “We don’t know the impact of that on the other side of the border or vice versa. We don’t know the quality of that water. We don’t know who has been drilling wells or for what use. We don’t know what has possibly been pumped into these aquifers. And, we don’t know how much water we have left.”

Some groundwater maps and databases run by state and federal agencies have blank regions around the border, providing incomplete records of border groundwater supplies that are integral to the regions’ communities and economy, she said.

“My undergraduate and master’s studies were in diplomacy, and I’m a diplomat by training,” Sanchez said. “So, when I started studying groundwater for my doctorate, and I’d examine these maps and models that just stopped at the border — it didn’t make any logical sense. So, we started from scratch.”

Mapping 121,500 square miles of hydrology

The shared aquifers underly more than 121,500 square miles of borderland and each country and state has a different methodology for determining and defining aquifers. To address this, Sanchez’ research team began this massive undertaking by creating a unified identification methodology and started their transboundary aquifer count at zero.

“Every point in that map was a decision we had to make, based on nature and scientific data,” she said.

To define the aquifers, the team first studied the regions’ geological formations, spanning both sides of the border, then the type of formations and their porosity.

“Our analytical method used geology, topography, lithography, geomorphology and hydrology to identify hydrogeological units (HGUs), and those HGUs that have good aquifer potential at the transboundary level,” Sanchez explained.

Accurate data and binational cooperation

“Establishing a framework for local groundwater management is my ultimate goal for this work, because of the major binational water security implications of future management of these shared resources,” she said. “But we weren’t able to get to that point over the last 10 years, and it’s going to take funding resources and binational cooperation to get there in the next 10 years.”

International borders over groundwater resources are a complex paradox, she said, because “boundaries don’t matter to natural systems.”

Sanchez said that scientifically, the next step needed is to evaluate how much water is in the aquifers and the quality of that water. Then, local and regional stakeholders can begin to work together towards mutually beneficial shared governance and management of the groundwater resources.

“Negligence has been the status quo,” she said. “But it’s only a matter of time until shared management has to be discussed.”

Story written by Leslie Lee, Texas Water Resources Institute