A backbone for science … and art

Texas A&M contributes to first-time, high-resolution, 3D scans of more than 13,000 animal specimens available online

A few years ago, a German researcher asked to borrow a preserved, 13-foot-long bigeye sand tiger shark from the extensive specimen collection maintained by the Texas A&M College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. Curators regretfully declined the request – shipping something that delicate, and that large, was too difficult.

Today, the researcher need not go away disappointed. A three-dimensional, research-quality digital copy of the shark’s skeleton is among the College’s many contributions to a first-of-its kind international compilation of virtual specimens. The openVertebrate Thematic Collections Network has gathered scans of more than 13,000 animal specimens and made them freely available to anyone with an internet connection, thanks in part to a $2.5 million National Science Foundation grant.

Curious about what the shark’s skeleton looks like? Or other specimens kept at the Texas A&M Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collections, BRTC, such as the Chinese alligator or elf owl? Want to use a 3D rendering of these specimens in a classroom exercise or art project?

“These are available to anyone for noncommercial use,” said Heather Prestridge, staff curator of the BRTC.

The facility, curated by staff and faculty of the Department of Ecology and Conservation Biology, is among the largest university-based natural history collections in the U.S., home to more than 1.3 million specimens, many of them stored in drawers or preserved in jars of alcohol arranged along row upon row of shelves. It is a place with a vast store of knowledge, but also a mission to protect the sources of that knowledge – the specimens – from wear-and-tear that could render them unavailable to future generations.

BRTC curators see the online database as a means of sharing that knowledge while protecting the specimens. A retired Australian schoolteacher and students at a Bryan art studio are among those who have already used BRTC-created scans, which formed the basis for artwork showcased at the Memorial Student Center’s James R. Reynolds Gallery.

“Access to something like this is really important in my world,” said LeAnn Hale, owner of Purple Turtle Art Studio. “It takes students out of the box of art having to be a certain way and lets them see things that they can use as inspiration to create.”

A digital solution to a centuries-old conundrum

The openVertebrate effort was born out of a difficult question the BRTC and many other collections and museums face: how to protect preserved animal specimens while still making them available. Just shipping specimens from one scientific institution to another can damage them. Shipping or travel can also be expensive enough to prevent scientists from conducting otherwise-valuable research.

Access can be a particularly tricky issue at the BRTC because the facility – a converted warehouse just off campus – preserves specimens for scientific study, not educational display. A specimen is either stored or is handled by scientists and students during research that inevitably causes wear and tear.

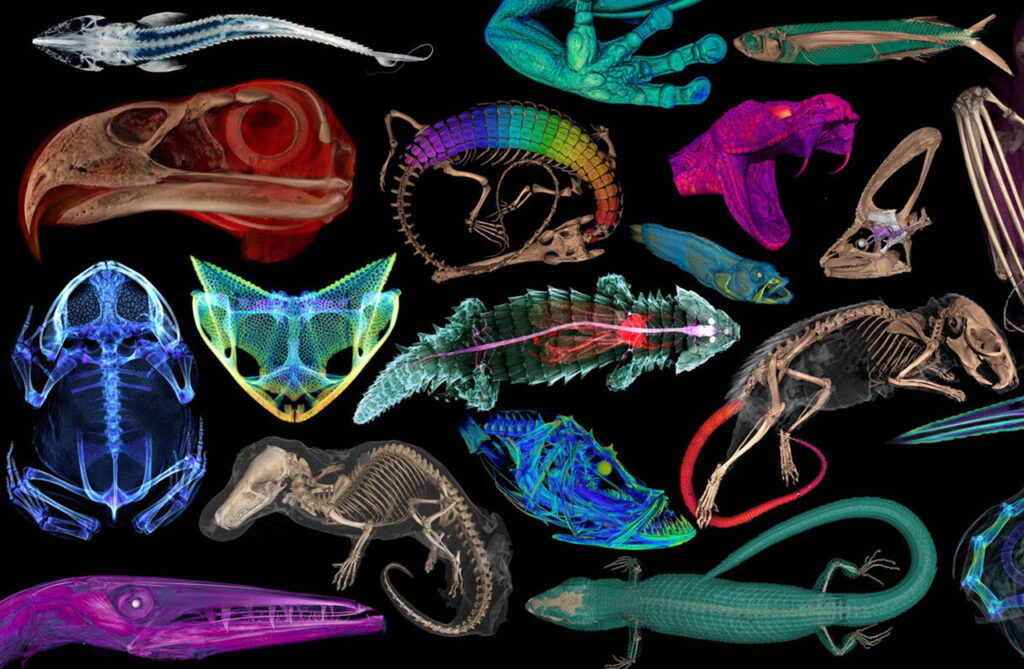

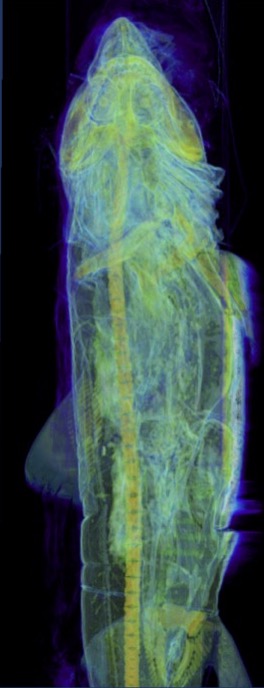

Computer imagery offers a solution to both the public-access and wear-and-tear conundrums. The openVertebrate project uses high-energy X-rays generated by CT scanners to enable scientists to peer beyond an animal’s exterior. The species scanned include fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Most scans were intended to reveal the specimen’s bone structure – hence the “vertebrate” in openVertebrate – but in some cases, researchers injected a temporary staining solution that allowed them to visualize soft tissues such as skin, muscle and other organs.

The specimens for the project came from 18 research institutions that ultimately joined the $3.6-million effort, which began in 2017. Its funding included both the $2.5 million from the National Science Foundation and eight smaller grants. The results were published March 6 in the journal BioScience. Prestridge is one of the co-authors, along with Kevin Conway, Ph.D., the curator of the BRTC’s fish specimens and a professor in the Department of Ecology and Conservation Biology.

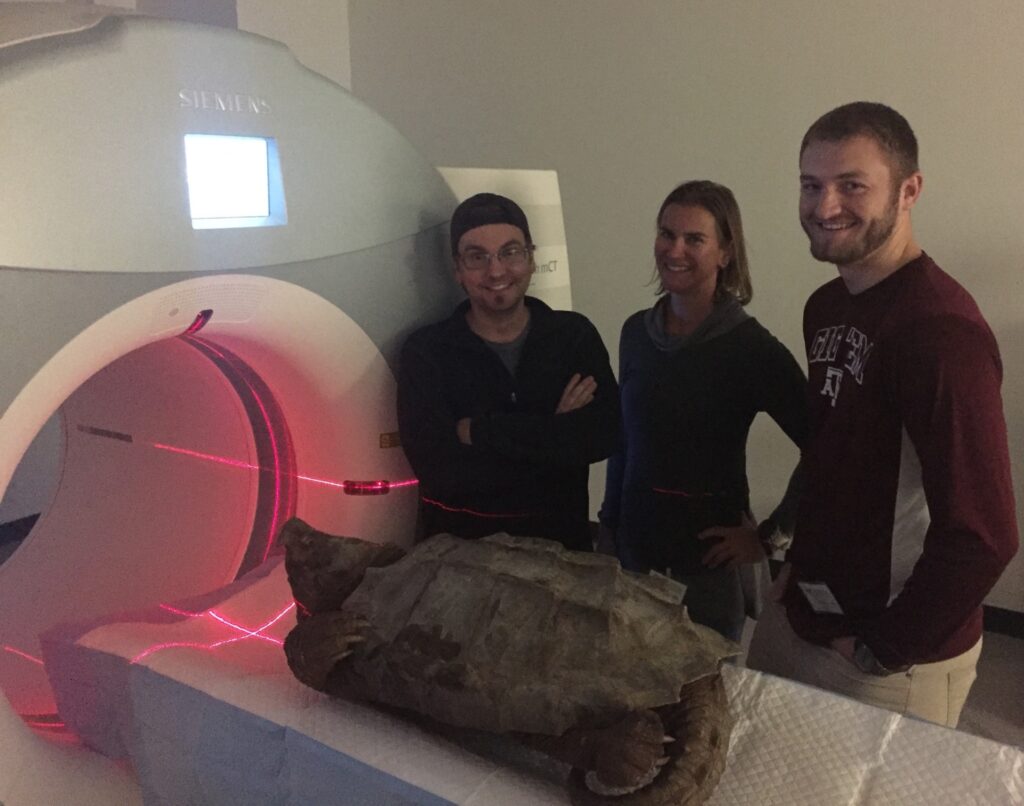

A chance conversation between Conway and one of the project’s early organizers led to the BRTC’s involvement in the openVertebrate project. Conway, Prestridge and students under their direction scanned 395 specimens, including rare species held at the BRTC: a Chinese alligator, a bald eagle and an ocelot – as well as the bigeye sand tiger shark specimen that interested the German researcher. Conway said the shark specimen is one of only two held by museum collections across the world for that species.

“There’s no way we could ship it,” Conway said. “And for someone to come here to study, it can get expensive. This project allows us to make the anatomy of these vertebrates accessible on a scale that wasn’t feasible before.”

Big scanner, big results

The BRTC does not have a CT scanner, so most of its specimens were shipped to the University of Florida or University of Washington for scanning. These specimens were on the small side; most research-grade CT scanners used to examine specimens can only accommodate something up to the size of a softball, Conway said, so larger species are consequently underrepresented among the world’s scanned specimens. Scientists studying large species have often resorted to scanning juvenile specimens and then made educated assumptions about an adult’s characteristics.

But the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, VMBS, happens to have a large scanner – one large and reinforced enough to accommodate creatures as large as horses, cattle, llamas and lions. Texas A&M became the place to scan large specimens – basically, anything bigger than a watermelon. Together, Conway, Prestridge and their students scanned about 50 such specimens at the VMBS.

Conway said the BRTC’s alligator gar is among the most viewed of the specimens he scanned. This group of fish species has hardly changed over the past 120 million years, offering a window into an era long passed. Seahorses, ocelots and solenodon, a venomous mammal, are also popular picks.

Each CT scan is converted to a data set – basically, thousands of images of a specimen, recorded digitally – and each data set is available through MorphoSource, an online data repository. Accompanying each data set is the name of the researcher who uploaded it; those interested in downloading a set can contact that researcher for permission. Prestridge said requests for BRTC-created scans can also be sent to [email protected]. Organizers require users to seek permission in part to track how the public is benefitting, per a National Science Foundation requirement.

Conway said those proficient in the software can, in many cases, not only observe but virtually measure, dissect or 3D print a specimen.

Which is what attracted Erwin van der Minne to the project.

Where science meets art

Prior to the openVertebrate effort, the BRTC would occasionally host artists who wanted to use a specimen as the basis of a project. Museum curators consider such collaboration part of their mission but can spare only so much time accommodating the artists amid the myriad of responsibilities required to maintain the collections.

Separately, halfway around the world in Australia, van der Minne has been preparing and assembling animal skeletons for half a century. With the rise of the internet and modern software, he moved into digital sculpting. Now a 61-year-old retired math and science teacher living in Cockatoo, in the hills southeast of Melbourne, he uses CT-scan data stored in online repositories as the basis for 3D digital sculptures that combine his passion for art and knowledge of the natural world.

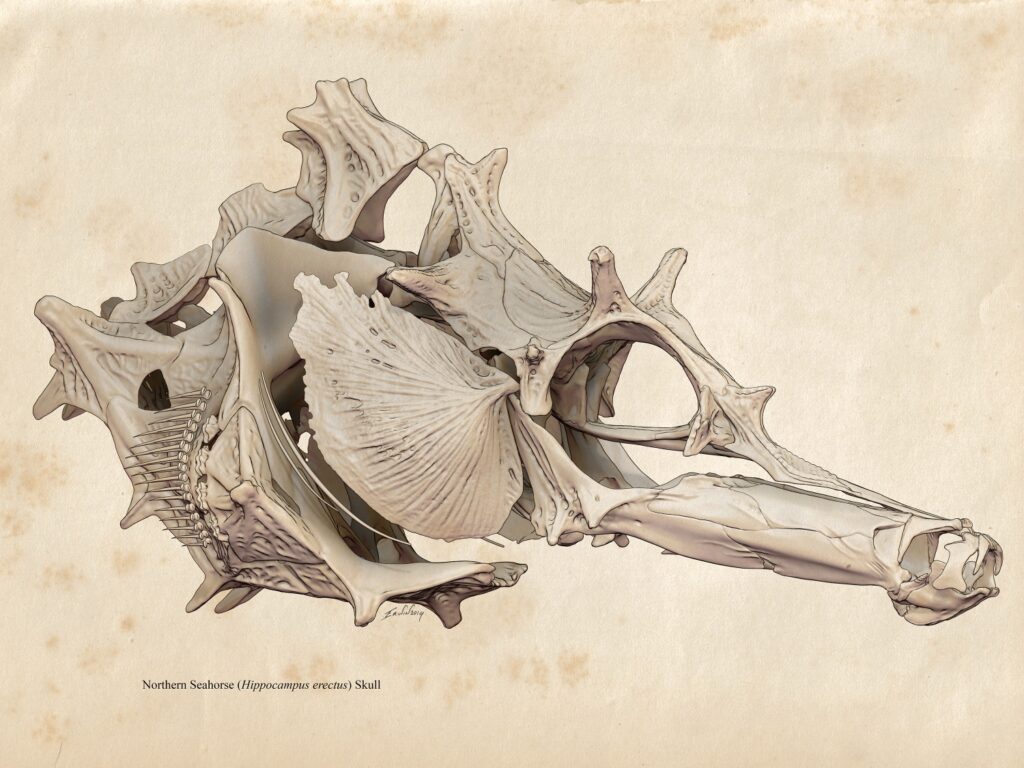

The openVertebrate project bridged the 9,000 miles separating the BRTC and van der Minne. A few years ago, while searching MorphoSource, he found a CT scan of a lined seahorse, which led him to Prestridge, who in turn used the virtual 3D sculpture he created of the skeleton in her classes.

To ensure that the labeling and features were correct, van der Minne contacted Conway, who found that little information is available on seahorse skulls. Conway and van der Minne have been working together since then to create an anatomical atlas of the seahorse skull, identifying each bone and illustrating how they fit together.

“The online archives are a treasure trove to me,” van der Minne said. “I have about 10 to 15 projects on the go right now.”

The lined seahorse digital sculpture was included in a 2021 Texas A&M Foundation-funded exhibit that the university’s Innovation[X] grant program put on at the James R. Reynolds Gallery. Revival: Visualizing Natural History Specimens in Art and Science also included eight pieces created by Bryan-College Station children taking classes at Purple Turtle Art Studio.

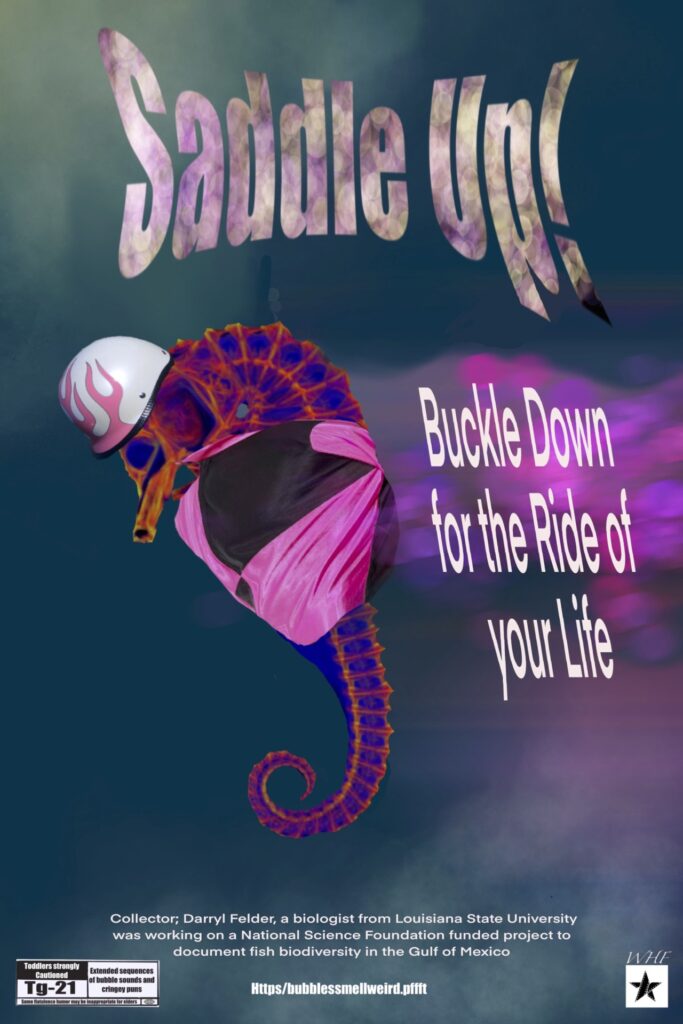

Hale, the studio owner, has known Prestridge for more than a decade. They have partnered on several projects. Access to the BRTC’s openVertebrate virtual specimens gave the Purple Turtle students, who were ages 9 to 17 at the time, an opportunity to combine science and art while learning computer skills. Guided by Russell Marcontell, an art professor at Sam Houston State University who works with Purple Turtle, the students incorporated the specimens into noir-style faux movie posters. The skeletons add a surreal element.

Hannah Hailey, then 16, created a poster with a misty, brooding lagoon for a movie titled “Lake Al.” The BRTC’s Chinese alligator inspired the title and poster design, Hailey said in an audio clip accompanying the piece’s Reynold Gallery debut. She incorporated the gator’s skeleton into numerous aspects of the poster, from leaf clusters to tree limbs to the shoreline, yielding an image with an ominous feel.

William Hale, then 13, based his design around the rendering of a lined seahorse. He built the poster and storyline around a pun – the seahorse is wearing a jockey helmet and jacket because it embarks on a journey to compete at the Kentucky Derby.

And Norah Stanfield, then 9, named her piece Bite. The title and image are inspired by the jaws of an ocelot. She chose that animal because she likes cats, and she learned that ocelots, like cats, are felines.

Hailey, the artist who used the Chinese alligator in her poster, is now an Aggie, class of ’27.

“It was very cool for the kids to realize this kind of thing is accessible to them,” Hale said. “You never know who’s going to go, ‘this is fascinating, and I want to learn more about it.’”