What are PFAS?

‘Forever chemicals’ a persistent environmental problem, likely risk to human health

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, PFAS, are a category of thousands of manufactured chemicals, defined by their bonds between carbon and fluorine molecules, one of the strongest known chemical bonds. While scientists have known of PFAS since the 1940s, there are still many unknowns about them and their long-term effects on people and the environment.

However, in recent years, more research has revealed that PFAS are found in our air, water, soil and food. Sometimes called “forever chemicals” because their strong chemical bonds make them persist in many environments, PFAS have been shown in research to have potential health consequences as they possibly build up in the human body.

“We live on a planet where every component interacts,” said Susie Dai, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology at Texas A&M’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. “People are concerned not only about their water, but also about local crops and animals that are produced by using that same water and become part of our food supply.”

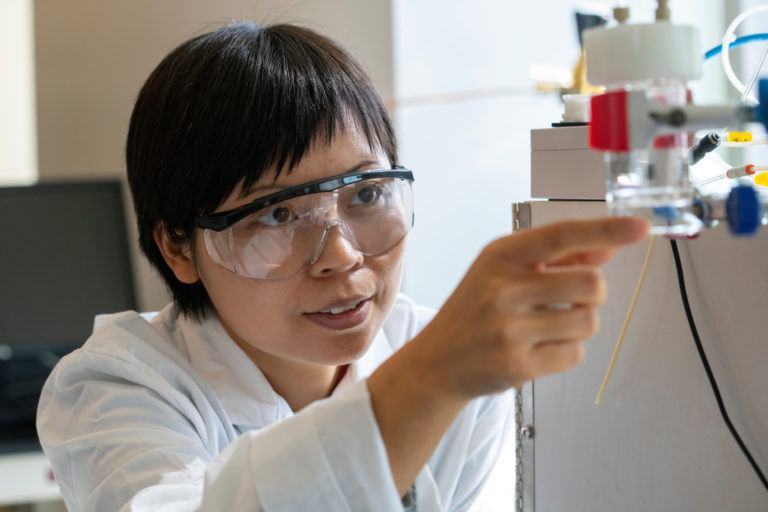

Research teams such as those in Dai’s lab and that of Yina Liu, Ph.D., professor of oceanography at Texas A&M University and Texas Water Resources Institute, TWRI, Faculty Fellow, study PFAS in the environment, wildlife and food products.

Forever chemicals explained

Although there are still some scientific unknowns about PFAS, here is an introduction to the science behind them:

— PFAS refer to a large group of manufactured chemicals used in numerous industries and products Common examples of PFAS include chemicals in nonstick cookware, firefighting foam, microwave popcorn bags and pizza boxes. PFAS are highly heat resistant and repel both water and oil.

— There are two different classifications of PFAS: short-chain or long-chain, depending on the amount of carbon atoms found on the chain of the PFAS, said Xingmao “Samuel” Ma, Ph.D., associate professor in the Zachry Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Texas A&M and TWRI Faculty Fellow. Depending on their chemical make-up, long-chain PFAS compounds are typically defined as having more than six to eight carbons, while short-chain compounds usually have less than six to eight carbons, Ma said.

— Long-chain compounds have different rates of solubility, transport and toxicity than short-chain compounds, and environmental regulations are different for each. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA, defines long-chain perfluoroalkyl carboxylate chemical substances, PFAC, a subset of PFAS, as having “carbon chain lengths equal to or greater than seven carbons and less than or equal to 20 carbons.“

— According to an EPA study, landfills and waste disposal sites have some of the highest levels of PFAS. Up to 95% of landfill samples tested positive for high levels of PFAS. Military bases and airports also tend to be places with higher PFAS levels, due to their use of fire-extinguishing foam.

— Center for Disease Control and Prevention studies have shown that some PFAS are known to have a long residence time in the body. It was previously thought that short-chain PFAS moved through the body faster than long-chain PFAS, but recent studies have revealed that short-chain PFAS can more easily build up and stay in our bodies.

— According to the EPA, multiple peer-reviewed studies have found that exposure to certain levels of PFAS may lead to negative health effects, and an increased buildup of PFAS in the body may also lead to a decreased immune system and affect endocrine systems.

Understanding PFAS

As regulators and industries continue to grapple with the implications of PFAS, scientists like Liu and Ma are working to further our understanding of PFAS, and to develop deployable technologies to effectively remove PFAS compounds from environments entirely.

For more information on PFAS:

- Pervasive Problem: Texas A&M researchers discussed PFAS and water in the Winter 2020 issue of txH2O magazine.

- Texas A&M AgriLife develops new bioremediation material to clean up ‘forever chemicals’: learn about PFAS bioremediation research by Dai.

Story written by Cameron Castilaw, Texas Water Resources Institute