Mosquito populations boom after rains

Tips on mosquito types and ways to prevent, control and repel

A rain event will often soon be followed by an explosion in the mosquito population. A Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service expert has information on the types of mosquitoes that may appear and tips on how to control or repel them.

Sonja Swiger, Ph.D., AgriLife Extension entomologist and professor in the Department of Entomology in Texas A&M’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, said biting mosquitoes are a seasons-long problem that can change with the environment.

Swiger, who is based in Stephenville, said the type of mosquito present and whether it represents just an annoyance or a possible disease vector likely depends on such environmental conditions. Also, water availability and type — such as fresh, clear floodwater in ditches, a container collecting water or stagnant puddles left behind from previous weather events — all contribute to what sort of mosquito might be visiting you and your family.

Recent hot and drier conditions are raising concerns among health officials about the potential for rising populations of vector mosquitoes. Swiger said one case of malaria has been reported in Cameron County and public health officials will be monitoring for West Nile virus as well.

The mosquito boom

Rainfall can significantly contribute to a boom in mosquito populations, especially with multiple storm systems that saturated and flooded areas around the state, Swiger said.

“Due to the recent, and in some locations continuous, rains, people should expect to see quite a bit more mosquito activity,” she said. “While the primary concern about mosquito species should be the disease carriers, all this rain has created plenty of habitats for floodwater and container species.”

Swiger divides mosquitoes into three categories – floodwater, container and stagnant – and they typically emerge in the order related to the breeding environment they prefer.

“Mosquitoes come in waves and can overlap as the season progresses,” she said. “It can help to understand what type you are dealing with, how to do your part to control them around your home and how to protect yourself and your family because we are in mosquito season.”

First wave: floodwater mosquitoes

Floodwater mosquitoes are the first to emerge after rain events, Swiger said. These mosquitoes are typically larger, more aggressive and more persistent biters from dawn to dusk.

Heavy rains saturate the ground and create standing puddles in ditches and low spots in fields and lawns. Floodwater mosquito larvae quickly emerge after water becomes available. Eggs are placed there by females the previous year or with the previous rain event and wait for water to return. Sometimes these eggs can wait two to five years before hatching, depending on the species, Swiger said.

“The potential for standing water could make their habitat more widespread, which will make them a greater issue for more people than normal,” she said. “Any location that is holding water, even in grassy areas, could be a breeding ground.”

Swiger said females lay their eggs in the moist soil around puddles, and either more larvae emerge with the continuous rains or they will go dormant and wait for water to return. Subsequent rains can wash larvae downstream but can also trigger dormant mosquito eggs.

Second wave: container mosquitoes

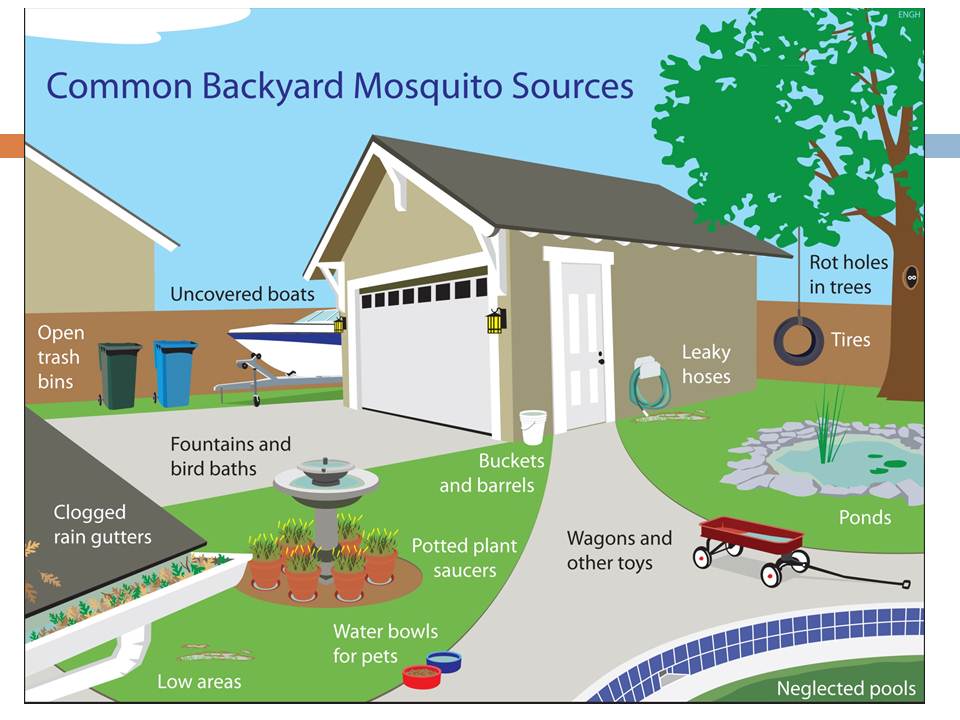

Container mosquitoes, which include the Aedes species, identified by its black and white body and white striped legs, typically emerge next. Female mosquitoes lay eggs in anything holding water – from tires, buckets and wheelbarrows to gutters, unkept pools, pet dishes and trash cans. They prefer clearer, fresher water, and females constantly look for good breeding sites.

Container mosquitoes like Aedes are daytime feeders but can be opportunistic at nighttime when large groups of people gather, Swiger said.

“Any time after a rain, it is good to make a round on the property to look for anything that might be holding water,” she said. “It just takes a matter of days for these mosquitoes to go from egg to biter, so they can become a problem pretty quickly.”

Third wave: Culex mosquitoes

Culex, a mosquito species that prefers stagnant pools of water with high bacteria content, typically emerge as waters recede and dry summer conditions set in and create breeding sites in low-lying areas.

They are the disease-carrying species that concern the public and health officials, Swiger said.

It is not easy to forecast their emergence because their ideal environment can be washed away by additional rains or dried up by extreme heat and drought, Swiger said. Vector programs and health departments monitor the presence of these Culex mosquitoes and the West Nile virus from May to November.

In rural areas, bogs, pooled creek beds or standing water in large containers such as barrels, trash cans or wheelbarrows can make a good habitat for Culex. In the city, similar pools in dried-up creeks or other low spots can create breeding sites, but most urban issues occur underground in storm drains where water can sit and stagnate.

“It’s difficult to predict when or where these mosquitoes might become a problem,” she said. “Widespread heavy rain makes it even more difficult to predict.”

Mosquito borne diseases

In Texas, there are cases of West Nile virus every year. Mosquito control efforts focus on managing the mosquitoes that carry this virus, and surveillance is conducted which allows the ability to watch the incidence of positive mosquitoes increase as the temperature increases. West Nile typically begins with birds and can be observed as it moves into the biting Culex populations and on to horses and then humans.

“Thus far, we have had 70 positive mosquito pools from 10 different counties in Texas but no human positives yet,” Swiger said.

Other diseases can be of concern to Texans, including dengue and malaria.

“This year, we have had a positive local transmission of both dengue and malaria,” she said. “Local transmission means the positive individual has not traveled to another country or location that has mosquito borne disease circulation.”

The dengue case was reported from Val Verde County, she said, and while there is some local dengue transmission from time to time, it is not often and most of the reported cases are travel cases.

The positive malarial case reported last week is the first known local transmission of malaria in Texas since 1994.

“While roughly 100 or so travel cases of malaria are recorded in Texas annually, we don’t expect there will be local transmission, so this is unusual,” she said.

Swiger said malaria is carried by Anopheles mosquitoes, which are more associated with permanent water and swamps. The pathogen is a plasmodium which infests the red blood cells of humans.

Protecting from mosquitoes

Swiger said reducing mosquito numbers in your location and using spray repellents are a good start for protecting from bites. Covering exposed skin with long-sleeved shirts and long pants will also help.

She also recommends repellents or mosquito-repelling products approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Spatial repellent devices like Thermacell are popular, as these devices emit chemical particles that create an effective barrier around a person or small space like a porch.

Plants like citronella, geraniums, lemongrass, lavender, lantana, rosemary and petunias have been shown to repel mosquitoes, but Swiger said the distribution limits effectiveness for protecting a space. The repellency is limited just to the plants and rarely keeps mosquitoes from biting humans.

Candles and other smoke-based repellents fall into a similar category as plants, Swiger said.

“Protecting yourself with any spray-on, CDC-approved repellents like DEET, picaridin, lemon eucalyptus oil, IR3535 or 2-undecanone is my best recommendation anytime you go outside for more than 30 minutes, but many mosquitoes will bite within seconds,” she said. “Personal protectants are the only certainty against bites.”

Swiger said pets should be removed from areas with mosquito infestations, remembering that mosquitoes transmit heartworms to dogs and cats. Small children should not be taken outdoors for extended periods if mosquitoes are an issue because they can have adverse reactions to mosquito bites, and spray products should be used sparingly on them, especially babies.

There are age restrictions for most repellents; no repellents on babies less than 2 months old, and do not use lemon eucalyptus oil on children 3 and under.

“This time of year, it’s just best to limit their potential exposure to mosquitoes,” she said.

How to control, prevent mosquitoes

Controlling mosquitoes after widespread, heavy rains is difficult because their habitat can be so unpredictable, Swiger said. Container mosquitoes are a bit easier if you can locate them and impact their habitat by dumping the water or treating it with granular or dunk larvicides.

“Empty containers filled with water as much as possible and look for standing water that can be drained or where dunk larvicides can be effective,” she said.

Sprays or barrier treatments that kill adult mosquitoes are another option, but effectiveness is limited, Swiger said. Products that homeowners can apply only last 24-48 hours. Professionals can apply longer-lasting barrier products – typically pyrethroid-based or organic products – but their effectiveness degrades with time.

Some groups and municipalities initiate mosquito abatement programs, especially when major outbreaks occur or mosquitoes become a health risk. These programs are an additional tool in the fight but are temporary, Swiger said. They typically spray at night to kill adult mosquitoes, and the residue burns off in the sunlight after dawn.

“Some cities and counties do a pretty good job staying on top of mosquito management, but it can be an overwhelming task, and weather can hinder effectiveness,” she said. “The best thing to remember is to protect yourself when outdoors for extended periods, reduce breeding sites as much as possible in your space and then be mindful of areas nearby that might become problematic.”